An architect's diatribe on Citi Field

Say what you will about Shea Stadium, at least it's an ethos.

To understand the New York Mets, you must understand Citi Field.

When Shea Stadium, the Mets’ home for nearly a half-century, reached the end of its useful life, the team’s owners — among the dumbest and most craven rich guys in the proud fraternity of Dumb, Craven Rich Guys that make up professional sports ownership — commissioned a new ballpark as a love letter to another franchise and time.

The Mets’ stadium doesn’t respect the Mets.

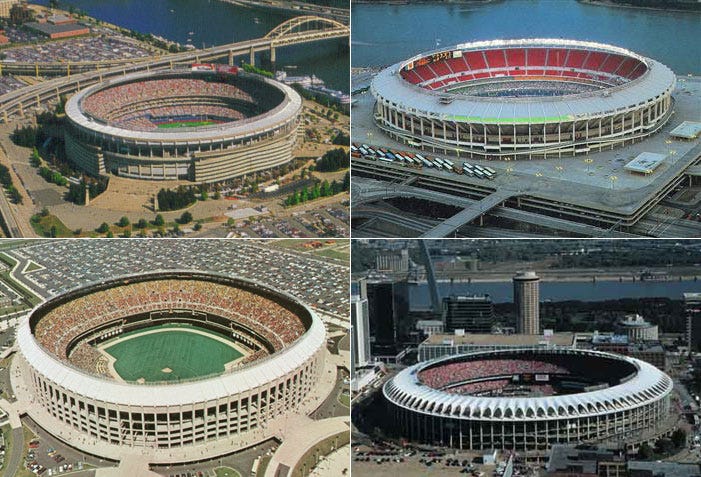

The so-called “cookie-cutter” stadiums of the 1960s are by no means above criticism. Shea Stadium in Flushing, Queens, Three Rivers Stadium in Pittsburgh, Veterans’ Stadium in Philadelphia, Busch Stadium in St. Louis, Riverfront Stadium in Cincinnati, Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, Jack Murphy Stadium in San Diego — save for a few superficial differences, they were more or less the same.

They were planned with the heavy-handed urbanism of the era, in many cases obliterating prime waterfront real estate, situated a completely scale-free, unwalkable manner. They were overly spacious and many seats were far from the field of play.

Despite the failings of their design, though, they at the very least represented an honest approach to address a need in a modern way. There was an attempt to create the future — even if that future were a car-centric, increasingly suburbanized one. They were civic stadia, built in a place for whatever teams would pass through them, not built to the whims of a specific businessman’s nostalgia.

When the New York Giants and Brooklyn Dodgers departed for the West Coast after the 1957 season, they were part of a larger shift away from the aging population centers of the Northeast. California represented progress. It represented the future. When, three years later, the National League awarded New York an expansion franchise that would replace the two clubs it had lost, the city had turned its eyes to the future as well.

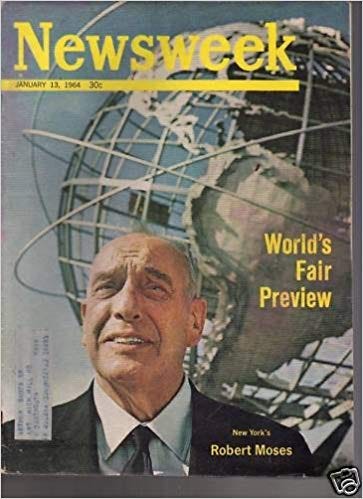

Planning was already in earnest for the 1964 World’s Fair, Robert Moses’ statement of intent about the city of the future. Moses, a man who spent a generation re-shaping the physical structure of the New York City metropolitan area, remains controversial — and for good reason. His designs were car-centric, classist, and often racist. He wiped neighborhoods clean in the interest of now-debunked notions of good urban planning. If he’d had his way, much of what we now know of as SoHo would’ve been sliced away to permit an expressway to pass through. In a direct sense, his my-way-or-the-highway approach to negotiating was partly responsible for the Dodgers’ departure, as he insisted that a new stadium be built on his preferred site in Queens, rather than in their longtime home of Brooklyn.

Moses had no lack for ambition or vision, however, and many essential elements of New York City’s landscape would not exist if not for his power brokering. Lincoln Center. The United Nations complex. A half-dozen bridges stitching the region today. And his Colosseum, Shea Stadium, a hulking ode to the future and a conscious rejection of the ballparks of the earlier era.

Shea, like its cookie-cutter cousins around the country, wasn’t a perfect place to watch a game. Long before Baltimore’s Camden Yards ushered in the era of baseball-specific, retro-themed stadiums, the design ethos behind the Mets’ home had been rebuked. Ballparks like Camden — and Jacobs Field in Cleveland, The Ballpark at Arlington in Texas, and dozens that would follow, harkened back to an earlier era. Many moved back to city centers, revitalizing (or claiming to revitalize) the downtown cores that planners like Moses had forsaken. These ballparks brought fans closer to the field, offered better sightlines and more amenities, and have largely been embraced.

There were cynical odes to the ballparks of the past in many of these — the Texas Rangers’ home a mad pastiche of Detroit’s Tiger Stadium, pre-1974 Yankee Stadium, Boston’s Fenway Park and Chicago’s Comiskey Park. The Houston Astros’ Minute Maid Park (originally Enron Field) included a hill in center field until they finally admitted the folly of that in 2016.

But perhaps none was as cynical in its attempt to emulate someone else’s history than Citi Field. Nakedly an ode to the Dodgers’ former Brooklyn home of Ebbets Field, Citi Field -- named after a bank at the height of the financial crisis, I have to emphasize -- tossed aside any notions of looking to the future, or even embracing its tenants’ own history. Fred Wilpon’s grand vision for the future of New York baseball was to attempt to rekindle the memories of his own Brooklyn childhood. What’s notable about Citi Field is that, more than most places, it does this with no attempt to recapture the context in which ballparks like Ebbets worked. Built in Shea’s parking lots, it’s still isolated from the urban core, 1930s cosplay stuck in 1960s planning.

The ballparks of baseball’s golden age gained their character from necessity -- sharp angles as they contorted into an awkward site, around railroad tracks or rowhouses. Citi Field emulates those angles when it’s got legroom to spare; it mimics the past for no reason other than empty nostalgia. On approach into LaGuardia or passing by on the Grand Central Parkway, it stands like a lonely movie set, jarringly out of context.

Alright, I’m done being a contrarian. It’s a perfectly fine place to watch a ballgame. I’ve been. I watched several innings of Mets-Cubs in between concessions runs and enjoyed a postgame Boyz II Men concert. It’s clean, comfortable, and the sightlines are great. I just can’t help but feel like something is lost when stadiums have abandoned any ambition, any attempt to innovate the ballpark of the future, and instead rely on nostalgia for a time many of us never saw. We could watch a Ken Burns miniseries if we wanted that. Citi Field tries so hard to tell us how great the Brooklyn Dodgers were, it almost forgets that the New York Mets play there.

But at least there’s a Shake Shack.

———

Thanks for subscribing to The Seventh Circle!

As a reminder, you don’t need to listen to The Seventh Circle Podcast to keep up with the newsletter, but in our entirely unbiased opinion, you should. This week, we talked about the frustrations of New York Mets fandom with David Roth of Deadspin, the foremost chronicler of our era, perhaps the person best equipped to discuss this maddening franchise and its place in our zeitgeist.

Episodes drop every Sunday night, and we’ve got some truly exciting guests and topics planned for you over the coming weeks. We’ll understand if you’re a read-only type, but hope you’ll give it a try if you haven’t already.

You can find us on Apple, Spotify, Stitcher, and pretty much any podcast app you can think of. Follow us on Twitter and Instagram at @CircleSevenPod, and please, if you enjoy the podcast, rate and review!

— Scott Hines (@actioncookbook)

(I am actually an architect, so I get to have Stadium Hot Takes.)