Ballparks of Uncertainty

Considering the future of sports stadiums in a pandemic-stricken world

Hello! Happy Monday. As you may have seen, The Action Cookbook Newsletter is now supported by Viewers Like You! Starting a week from today, two of the three weekly newsletters will be subscriber-only; one each week will remain free to all. Hundreds of you have already converted your free signups to paid subscriptions. I hope you’ll join me if you haven’t already; your support makes this newsletter possible, and I’m very grateful to you for it.

Now, on to it.

Despite the continued spread of the coronavirus pandemic in communities around the world, there’s been a real push in recent days to “re-open” society in many places. What exactly “re-opening” is means different things to different people, but it seems to center on a fervent desire to return to a semblance of normalcy: dining in at restaurants, shopping in person at retail stores, attending gyms and hairstylists — and having large public gatherings.

Of course, this includes sports.

The vast majority of professional and big-time amateur sports have been on hold since the first weeks of March, and only in a very few select places have they started to return. The KBO League has resumed playing baseball in fan-free stadiums in South Korea, a product of that country’s aggressive and largely-successful efforts to control the virus within its borders. Leagues in places with far worse infection statistics, though — like, say, here in the United States — have begun to make rumblings about how and when they might return, too. Players will likely return to their fields without fans in attendance first, but with ticket revenues making up 30-40% of some leagues’ income, there will soon be a push to bring fans in as well.

Perhaps you’ve seen some stories float around the internet lately with headlines like HOW STADIUMS ARE GOING TO CHANGE AFTER CORONAVIRUS or THIS IS WHAT THE BALLPARK WILL LOOK LIKE SOON. They’re reported as news, like something that’s really in the works, when in reality they’re wildly speculative exercises done by architects with no connection to the sports leagues.

I take several exceptions to this:

1) Hey, I’m an architect with no connection to any sports league!

2) I want in.

Last fall for SBNation, I wrote and illustrated a feature piece where I proposed ideas for the future of the American ballpark — thinking about how we could re-imagine stadiums to suit the changing needs and desires of fans. It’s a good piece, it got a great response, and I’m quite proud of it. At the time, however, I was not aware that those needs would include “avoiding a deadly viral pandemic”.

I’d like to take this chance to revisit the exercise and make a few new suggestions.

Some of these suggestions are drastic and reflect changes that would be made years down the road; some are immediate interventions that could be done this year.

Media outlets: When you aggregate this story, please credit me as “noted architectural sports visionary Scott ‘Action Cookbook’ Hines, who is handsome and a good cook”.

THIS YEAR

There’s no defensible logic for having a crowd of 30,000 or more people gather in one place before the development of a vaccine. It’s believed that a UEFA Champions League soccer match in Milan was responsible for one the worst local outbreaks in hard-hit Italy, as thousands of fans brought the virus back to the small town of Bergamo.

But what if, instead of one gathering of tens of thousands of people, you had hundreds of smaller gatherings in the same place at the same time? A simple matter of crowd control could limit the risk posed by a large stadium gathering.

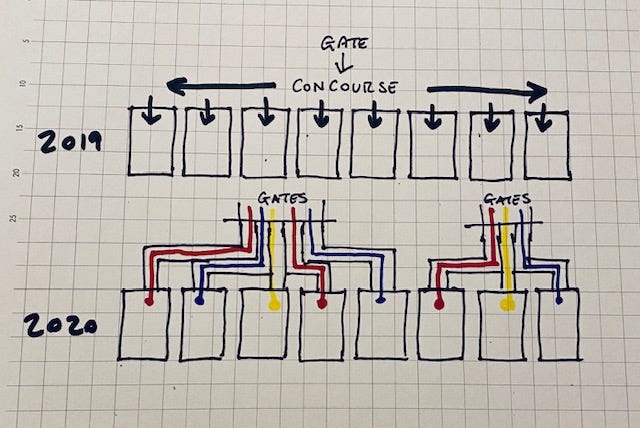

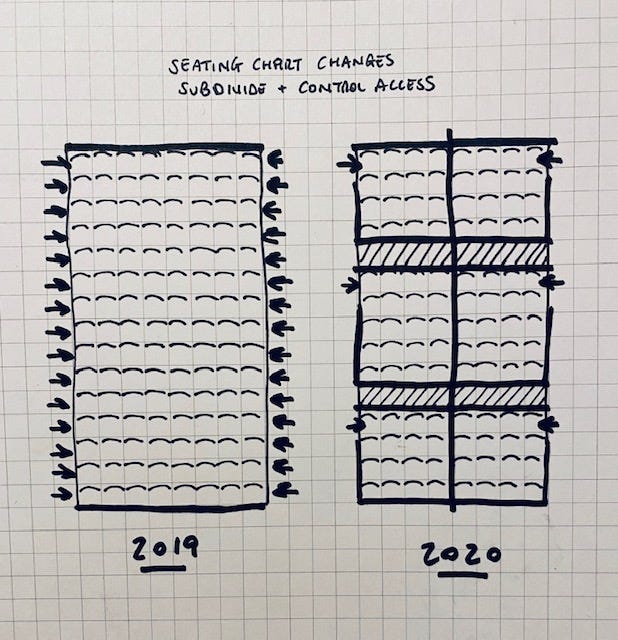

Take for instance Cleveland’s Progressive Field, my personal favorite Major League Baseball park. The stadium has a capacity of 35,000 seats. Fans can enter anywhere, circulate throughout the ballpark’s broad open concourses, and come into contact with thousands of people on their way to their seats. That same stadium has roughly 170 individual seating sections; that’s little more than 200 seats average per section.

Rather than a wide-open concourse and free movement throughout the stadium, corrals and cordons could funnel fans from newly-reconfigured, specified gates directly to their sections, which would be physically separated from each other by temporary partitions. (Any article like this has to mention plexiglass.) Temporary restroom facilities would be provided within those cordons; concessions would be ordered via smartphone app and delivered directly to one’s seat, a practice that’s already in place at many venues.

Rather than a gathering of tens of thousands of people, we’d end up with hundreds of smaller gatherings. Fans attending would provide personal contact information, allowing for quick contact tracing if any of their section-mates were to later fall ill.

If the stadium of 2019 was a shopping mall, the stadium of late 2020 might more closely resemble an airport terminal.

NEXT YEAR

If our current issues were to continue into another year, temporary solutions would have to give way to more concrete modifications to stadiums. The notion of breaking a stadium down to a collection of small gatherings could be made more robust, codified in the architecture itself.

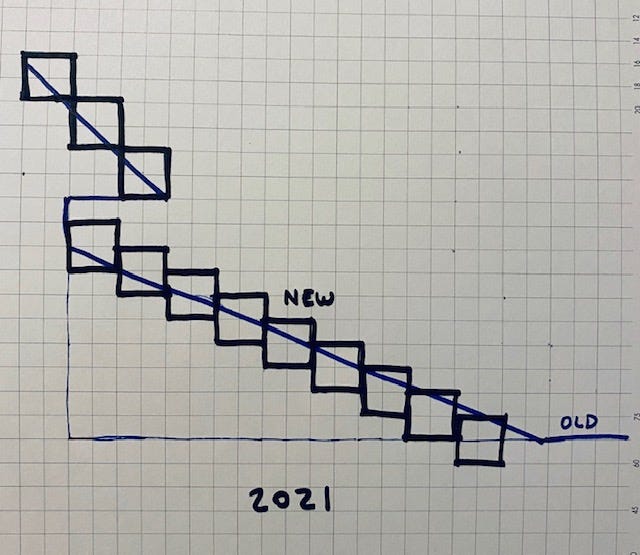

A major story in the evolution of the modern sports stadium was the rise of luxury boxes in the 1990s — beloved historic stadiums were deemed obsolete if they lacked the money-making private suites, and the design of new stadiums maximized them often at the expense of views from traditional seating.

Private suites will no longer be a luxury; they’ll be a necessity. Entire seating bowls could be gutted to remove open seating and replace it with self-contained suites. These need not be the pure-luxe suites for billionaires, and they’d have to be built quickly and affordably.

My answer? The same answer architects love to give to any question: shipping containers!

Pre-fabricated units could be stacked in reconfigured seating bowls, turning a stadium with a few hundred boxes to a stadium of entirely boxes. The same kind of careful funneling outlined in the first phase could be employed to get fans from the outside to their “seats” without closely interacting with large groups of other fans.

These boxes would be provided with essential utilities, private restroom facilities, and the like, but the interior configuration could be customized by individuals or supporters’ groups, building off of an idea I outlined in last year’s feature post.

THE YEAR AFTER AND BEYOND

If problems persist longer, the public’s demand for attending large in-person gatherings might wane permanently. At that point, we could see a significant shift, a fundamental re-imagining of what attendance at a sporting event means.

Fan-free stadiums won’t work forever; a single person watching a sporting event from home might find it a more pleasant experience than going to the stadium, but if there’s no one in the stadium, that television atmosphere suffers. It’s eerie without fan noise; players can thrive off the feedback of the crowd. The game isn’t the same without fan noise.

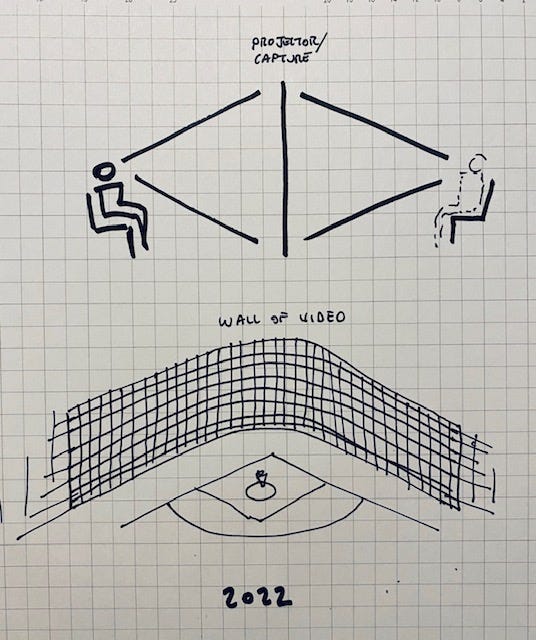

We’d have to go virtual.

I hate Zoom calls every bit as much as anyone else, but in a pandemic future we might find our home viewing situation changed to a two-way experience; a camera view directly from one’s seat; one’s image and sound projected back into the stadium. Imagine playing in front of a stadium-sized screen; it’s not so strange if you’ve been to a Dallas Cowboys game or a U2 concert, but instead of highlights or scenes of rustic Americana, it’s a live crowd on display.

We can take this idea even further, though. Staring at a single screen isn’t the same thing as in-person attendance; you can’t move around, experience the varied sights and sounds of gameday inside the stadium.

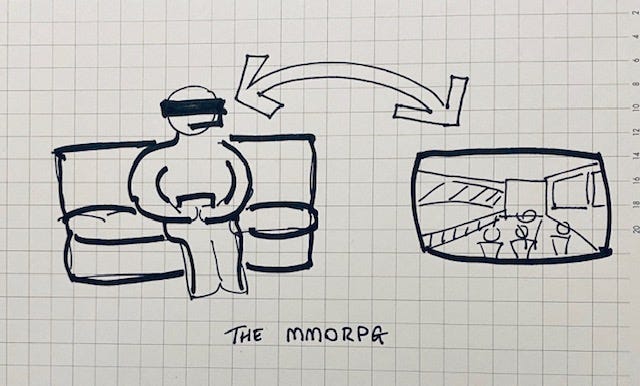

Gaming could be the solution.

An entire stadium could be modeled in incredible, interactive detail. From the comfort of their home, fans could not only watch the game but move about the stadium, changing their view and interacting with the digitized avatars of other fans doing the same thing.

A sports stadium becomes a massively-multiplayer online role-playing game. Fenway Park becomes its own Animal Crossing island.

But wait! Let’s take this even farther!

ONE STEP FURTHER

What if we accepted that sports are not going to make our problems go away?

I love sports as much as anyone; it’s felt like something’s been missing from my day for over two months now, and I long for the time when we can collectively experience an important game together again.

Sports is often touted as a vehicle for healing; Mike Piazza’s home run at Shea Stadium in the first game played in New York City after the September 11th, 2001 terrorist attacks rallying a battered city, that sort of thing. Sports don’t make the pain go away, though, and they’re powerless to stop a disaster that’s still ongoing.

At the time I write this, the number of people dead from the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States alone would fill the Rose Bowl; before long it’ll eclipse any stadium in the world. It’s silly to consider ways to return to stadiums when we’re still struggling to return to jobs, to shop for groceries, to see loved ones and make it through our days healthy, employed and solvent.

Sports are not a vehicle for healing; they are a symptom of that healing. Someday we will return to the stadiums; I will be able to share beloved traditions with my family and friends again, to thrill in the spirit of live competition and the camaraderie of a large, boisterous crowd. It will not be because we were clever enough to put in enough Plexiglass in the right places or provide six-foot buffers between seats.

It will be because this terrible moment has passed, and it will make it that much sweeter a return.

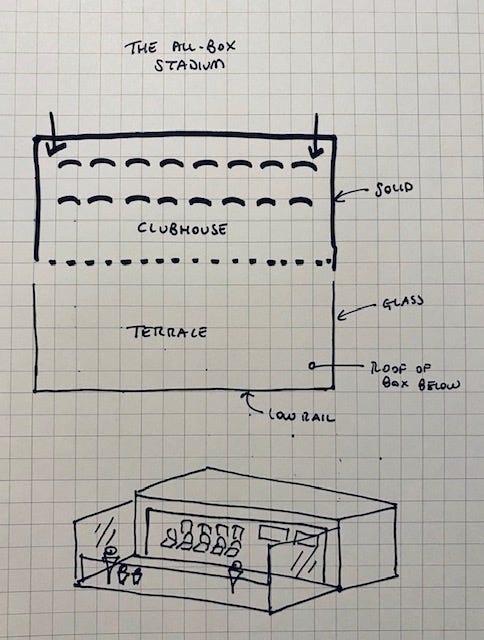

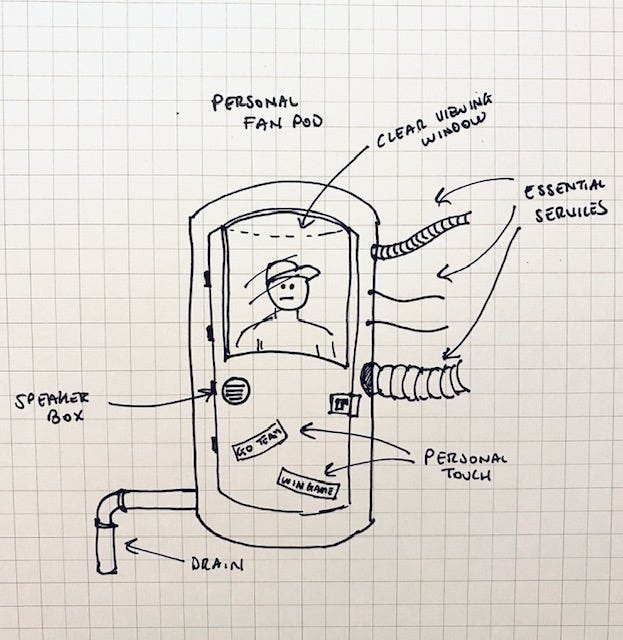

WELL THAT WAS A BIT OF A BUMMER, I THOUGHT YOU WERE GOING TO SUGGEST SOME KIND OF PERSONAL FAN-POD

Okay, fine.

A sealed and pressurized metal enclosure, with all the services a fan would need to stay alive and safe piped in and out. A clear glass viewing window providing an unobstructed view of the field. A speaker, so your roar can be heard outside of your perfectly-sterile bubble. Heck, you can even customize it, because this’ll be your very own pod! That’s right, teams will be happy to sell you a Personal Pod License; for a price in the low-mid tens of thousands of dollars, you’ll be the proud lessee of a factory-fresh fan terrarium all your own.

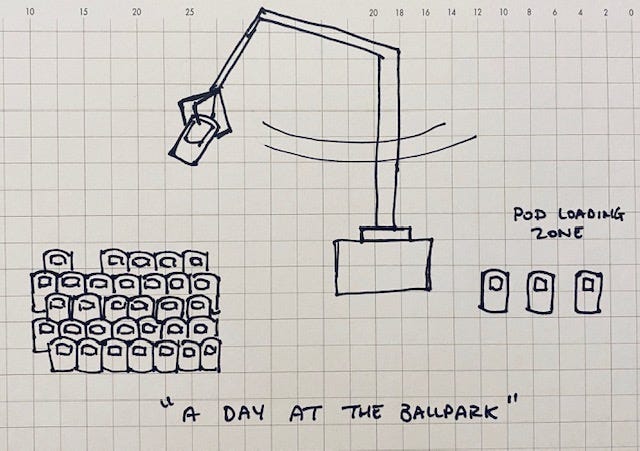

But how do I get it in and out of the stadium?

We’re still working out the details, but I envision some kind of giant claw machine.

Wow, that’s bleak.

You don’t know the half of it. That picture’s from a Mets game.

— Scott Hines (@actioncookbook)

I like the current plan of just deciding COVID is over, rushing everything back to normal, and everyone dying.