It was a dream season. It was the season I’d been waiting for my whole life.

If you looked at it on paper, you might think major college football is a meritocracy. There’s over one hundred teams at the top level, and every one of them is — in theory — playing for the same championship. The rosters are freshly stocked with new amateur players every year, and anyone could scrap and claw their way to the top in a given season.

Of course, most institutions that claim to be meritocracies aren’t really, and college football definitely isn’t. There’s a clear caste system, and upward mobility is rare. The last time a school won its first championship was in 1996. That is to say, for nearly a quarter of a century, no one who wasn’t already in the club has been allowed in.

In 2009, it seemed like that might change.

The Cincinnati Bearcats have had a long and mostly unremarkable history, playing over 125 years of largely-unloved football. While The Ohio State University, two hours northeast of them, was building one of the sport’s most storied legacies in the Big Ten Conference, the Bearcats hitchhiked through such illustrious destinations as the Ohio Athletic Conference, The Buckeye Athletic Association, The Mid-American Conference, The Missouri Valley Conference and Conference USA. For one year in the early 1980s, they were briefly relegated to Division I-AA due to lack of support. They were a basketball school, a commuter school, an urban school - the kind of school that doesn’t often compete at the top level of college football.

In 2005, they finally landed at what seemed like a real home: the Big East Conference. Paired up with comparable semi-powers like Louisville, Pittsburgh, West Virginia and Syracuse - and boasting an automatic bid to one of the four big postseason bowl games - the Big East offered the promise of respectability and growth. Of joining the big leagues.

This jump coincided with a pair of inspired coaching hires. First, national title-winning defensive coordinator Mark Dantonio from Ohio State, who would lead the Bearcats to two bowl games before departing for a lengthy and successful tenure at Michigan State. Then, a largely-unknown coach from Central Michigan University: Brian Kelly. Purple-faced with passion or rage on the sideline, in his first year in Cincinnati Kelly took the Bearcats to 10 wins for the first time in over 50 years. In his second year, that improved to a school-record 11 wins and a trip to the Orange Bowl.

His third season was when it would all come together.

Fresh off that trip to Miami, the Bearcats looked to be strong again in 2009, but it’s reasonable to say that no one expected them to do what they did that year. The season opened in Piscataway, a tough road game against Rutgers. Don’t laugh - this was in the brief and strange era where the Scarlet Knights were, dare I say, good. Head coach Greg Schiano had led them to four straight winning seasons, and they would turn in a fifth that year. I drove down from New York City to watch the game.

The Bearcats won 47-15, and the Rutgers fans headed for the exits long before the final whistle.

From there, they never blinked. Southeast Missouri State. Oregon State. Fresno State. Archrival Miami-Ohio. It was during a nationally-televised road win over ranked South Florida, one that brought their record to 6-0, that I realized this team might be blessed. Star quarterback Tony Pike left the game with an injury, and unheralded backup Zach Collaros entered to rally the Bearcats with a 75-yard rushing touchdown, his first of two scores. This team was unstoppable. Louisville. Syracuse. Connecticut. Tight wins over West Virginia and Illinois. The season would end with a de facto conference championship game on the road against #15 Pittsburgh, with the winner getting the Big East’s automatic bid a BCS bowl game - likely the Sugar Bowl. Everything was coming together; just beat Pitt and they’re in.

Flash-forward to just before halftime at Heinz Field, and the Bearcats trailed by 21. They needed a hero.

Mardy Gilyard had a story worthy of the hero’s journey. He’d come to Cincinnati in 2006, under Mark Dantonio. He didn’t attend class, and his grades reflected it. Dantonio revoked his scholarship, leaving Gilyard on the hook for tuition bills that he couldn’t pay. He spent months bouncing between friends’ couches and floors, sometimes sleeping his in car in the middle of the Cincinnati winter. He stuck around. He didn’t go home to Florida. He stayed around. He worked construction. He fought and persevered and earned the attention of the new coach, Kelly, who invited him back to the team.

By 2007, he was a full-time starter. By the next year, he was a star. He put in back-to-back 1,000+ yard receiving seasons in 2008 and 2009, and if there was anyone who could dig the Bearcats out of this hole in Pittsburgh, it was the young man who’d climbed back from much worse.

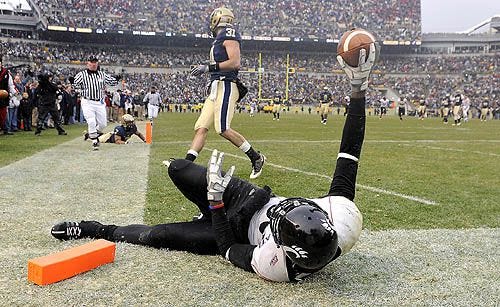

With seconds left in the first half, and Pitt staked to a 31-10 lead on a Dion Lewis rushing touchdown, Gilyard took the ensuing kickoff back 99 yards for a score. Early in the third quarter, Pike - back from his injuries - connected with him for a 68-yard score. The improbable Bearcats rallied so furiously, victory almost seemed a foregone conclusion when Armon Binns pulled in the winning score from Pike with 33 seconds remaining. 45-44, Cincinnati.

Twelve regular season games, and twelve straight wins. Unranked in Week 1, by Week 12 they’d reach #5 in the polls. A perfect season, capped by a thrilling, come-from-behind, last-seconds win on the road in the swirling snow. This year they weren’t going to settle for just playing in a major bowl game - this year there was - improbably, unbelievably - an outside chance of playing for the national title itself.

The Pittsburgh game - and the Bearcats’ perfect 12-0 regular season - ended in the early afternoon on December 5th, 2009, and the polls looked like this:

Florida

Alabama

Texas

TCU

Cincinnati

Boise State

Three traditional powers clustered at the top, and three upstart outsiders nipping at their heels. Florida and Alabama would play that evening in the SEC Championship Game, guaranteeing a loss for one of the two. TCU was idle, having closed their season a week prior with a resounding win over 1-11 New Mexico. Boise State would close their season hours later with a similarly thorough and statement-free trouncing of 3-10 New Mexico State.

At the time, “the computers” played a large factor in determining the final rankings - a somewhat opaque formula that purported to consider a wide range of factors, especially the strength of one’s schedule. Cincinnati defeating #15 Pittsburgh on the road would surely give a boost that would plant them firmly above the smaller-conference schools’ home wins against nobodies.

That left Texas.

Saturday night, December 5th, 2009, #3 Texas faced their final hurdle before a berth in the National Championship Game against Alabama, who had polished off the defending-champion Florida Gators moments prior. All that stood in their way were the 21st-ranked Nebraska Cornhuskers in the Big XII Championship Game, to be held in the brand-new Cowboys Stadium outside Dallas.

For a Cincinnati fan watching that night, it would have been foolish to hope that Nebraska could pull off the upset against Texas. The Cornhuskers were 9-3. They had won their division, the perpetually-weaker Big XII North, seemingly by default. They’d tallied a single win against a ranked opponent, the #24 Missouri Tigers, and had losses to Virginia Tech, Texas Tech and Iowa State.

Texas, meanwhile, had stormed through their schedule with relative ease, starting the season #2 in the country and rarely seeming threatened with much of a drop from there. At the center of their success was CW-teen-drama faced quarterback Colt McCoy, who’d broken many of the school’s passing records as a junior before returning for a championship run in his senior year. By the end of 2009, he would hold the NCAA record for wins by a single quarterback. McCoy was the kind of quarterback who wins championships; Texas was the kind of school he’d play at.

Nebraska should have posed no issue for McCoy and the Longhorns; but college football is a sport that has no use for the word should. Texas had scored at least 34 points in 11 of their 12 games to that point; by the waning moments they’d mustered only 10. McCoy hadn’t been sacked more than four times in a game that season; he was driven to the turf nine times that night, half of those coming at the hands of Nebraska’s dominant, ferocious pass-rusher Ndamokung Suh. The Huskers had only mustered a little over one hundred yards of total offense, but clung to a 12-10 lead with 1:44 remaining for the Horns to mount a final, desperate drive.

On first down, McCoy connected over the middle with his favorite target, sixth-year receiver Jordan Shipley, for a 19-yard gain. A horse-collar tackle by Nebraska’s Larry Asante would add a 15-yard penalty to the end of the play, bringing Texas suddenly within striking distance at the Nebraska 26. They were in field goal range, and they were going to burn the clock.

On the ensuing first down, McCoy kept the ball for a two-yard loss. Thirty-eight seconds.

On second down, he scrambled but held on again, losing another yard. Twenty-three seconds. Texas’s reliable kicker, Hunter Lawrence, warmed up on the sidelines for a long-but-makeable game-winning kick. They weren’t going to leave any time for Nebraska to respond after the the kick.

Third down. Texas let seconds run off the game clock before the snap. Ten. Nine. Eight. Seven. Snap. McCoy rolled right. Five. Four. Sound coverage. Three. Heaved a pass out of bounds. Two. One.

The pass lands. The clock reads 0:00. Nebraska players rush from the sideline. Coach Bo Pelini extends his arms in apparent victory, while Texas’s Mack Brown screams at the officials.

I’m in disbelief. Unbeatable Texas just lost. Cincinnati’s going to jump to #2 in the bowls. Little, unloved, disrespected Cincinnati is going to play for a national title. Cincinnati, five years out from playing in the Conference USA against the likes of Southern Mississippi and Alabama-Birmingham, are going to play Alabama-ALABAMA. Cincinnati, who was excited two years ago to play in the PapaJohns.com Bowl, is going to play in the Rose Bowl. I’m going to empty my bank account and go to Pasadena. The mountains. The sunset. New Year’s Day. The Tournament of Roses Parade. We’re in. We made it.

“The previous play is under further review.”

Several excruciating moments of uncertainty.

“After further review, there is one second left on the game clock.”

I’m stunned. They’re going to get another chance.

Hunter Lawrence comes out for a career-long-tying 46-yard field goal attempt. Pelini, never known for decorum, harangues the officials. McCoy hangs his head in prayer on the bench. Lawrence lines up on the left hash mark; Pelini burns a time out in a last-ditch attempt to ice him. They set again. One second. Lawrence’s kick sails up, hugs left, nearly sails out—

—and skirts just inside the left upright. Time expires. Texas celebrates. Texas is going to Pasadena. Cincinnati isn’t.

Doors close.

In the days and weeks and months to come, the impact of that second seems to ripple out. Cincinnati accepts a bid to play against Florida in the Sugar Bowl, both a tremendous milestone for the program and a significant disappointment, given what had almost happened. Before that game arrives, Brian Kelly accepts the head coaching job at Notre Dame. Cincinnati is demolished in the Sugar Bowl behind massive performances by future minor-league baseball player Tim Tebow and future triple-murderer Aaron Hernandez.

Six months later, Nebraska rebels against Texas’s Big XII hegemony and accepts an invitation to join the Big Ten. Conferences begin a multi-year riot of realignment. Missouri and Texas A&M follow Nebraska out the door, leaving for the SEC. The Atlantic Coast conference poaches Syracuse and Pittsburgh from the Big East.

Within three years the Big East football conference has dissolved, replaced by something called the American Conference. Nearly every team departed for greener pastures. Cincinnati remains, in a conference that looks suspiciously like the one we were so excited to graduate from ten years prior. The Bearcats put in a remarkable comeback season in 2018, winning 10 games. Their reward? A mid-tier bowl game. Even if they’d gone undefeated, teams from the American Conference don’t get to play for titles. Ask Central Florida.

Is it folly to say that that one play—one second—could’ve changed all that? Maybe. But would Brian Kelly have departed for Notre Dame—a dream job for anyone, let alone an Irishman named Brian Kelly, for crying out loud—with the chance to win a national championship on the line?

Would Nebraska have felt more comfortable in a conference they’d just won, more likely to stand up to Texas’s dominance in internal affairs, and not have bolted for the Big Ten? Would Texas, Oklahoma, Oklahoma State, Colorado, Texas Tech and Texas A&M have taken the widely-reported offer to join the Pac-10 and create the first true super-conference? Would the Big East, empowered by a national title berth, have poached the ACC, instead of the other way around? (This was, unbelievably, a real possibility at one point.)

Would Cincinnati, fresh off the biggest stage in college football, still have been left holding their hat when the sport’s tectonic plates shifted? Or would they have sealed their place in a big-time future that once seemed nearly in reach?

One second can make all the difference.

—Scott Hines (@actioncookbook)