Major League 2 is, by any reasonable metric, a terrible movie.

It checks every box of an unnecessary sequel. The plot is a complete rehash of Major League (1989), albeit with a handful of wacky new characters awkwardly inserted into the cast. The carryover characters have baffling new arcs. The biggest-name star in the cast couldn’t be persuaded to return, and was replaced with an actor who doesn’t look anything like him. They inexplicably try to pass off Baltimore’s Camden Yards—one of the most recognizable stadiums in American sports—as being in Cleveland. It holds a 5% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, which is a full twenty percentage points worse than Hillbilly Elegy.

(Major League 2 is one of my favorite movies of all time.)

This is not a recommendation, to be clear. Unless you were a 12-year-old boy living in Cleveland when the movie came out, you will likely see it as every bit the cinematic travesty that it is. If you have not already seen it, please do not go and watch it: it will only reflect worse on me. Despite all its forgettable gags and formulaic turns, though, there is one truly inspired performance in the film, and that’s Randy Quaid’s turn as Johnny, a loudly disaffected bleacher bum.

As someone who has spent four decades living with the frustrations of being a Cleveland sports fans, I have rarely felt more represented on film than by this man. Johnny spends most of the movie in a state of protective doomerism, one that feels quite familiar when you’ve spent decades seeing your team not win.

(At the time Major League 2 came out, Cleveland had not won a World Series in 46 years. As of this writing, that streak stands at 75 years, the longest active championship drought in North American professional sports for a single team in the same city.)

When you’ve got that kind of historical track record, it’s understandable that you might not want to get your hopes up. It’s a heck of a lot easier to just say “they’ll blow it in the ninth!”

There’s a lot of reasons to be pessimistic as an American today.

I’m 42 years old. I was a sophomore in college when terrorists crashed planes into the World Trade Center and Pentagon, murdering thousands of innocent people. Not long after that that our government started a series of wars that lasted nearly two decades and killed countless more, among them thousands of young American servicemen and women. I was two years of out college—just starting to get my feet set in a career—when the economy collapsed. Like millions of others, I lost my job, and was unemployed or underemployed for years thereafter. The coronavirus pandemic itself may not have been preventable, but the fumbling, selfish response to it surely cost many lives that could’ve been spared. Peppered in between all of these supposedly once-in-a-lifetime things, worsening wildfires and hurricanes and all manner of other extreme weather events have made it harder and harder to deny that climate change is happening—not in the theoretical future, but right now.

Oh, and in the middle of all of this, the worst person in American history became president, a position he used to enrich himself and his cronies while denigrating virtually every good thing the country is supposed to stand for—and despite two impeachments, an insurrection and a criminal conviction, he stands a reasonable chance of retaking that position and enacting a raft of regressive policies intent on rolling back a half-century of social progress in this country.

It’s not great!

And yet, despite all this, I’m optimistic.

This isn’t head-in-the-sand optimism, mind you; I’m clear-headed about the challenges we face. Climate change isn’t going to go away, and it’s going to take huge and concerted efforts at all levels of society both to deal with the damage already done and to prevent it from becoming worse. The federal judiciary is stacked at all levels with extremist political hacks bent on kneecapping any progress made on the major issues that affect us. This country is absolutely saturated with guns and anger, to the point where we can’t go to school, work, the store or a concert with full confidence that we’ll come home.

Not that long ago, I was one of those people who’d happily cherry-pick optimistic quotes from Martin Luther King Jr. while mostly ignoring the ones with concrete directives and uncomfortable truths; that is, I willfully misinterpreted “the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice” to mean “you know, things are probably going to work out fine”.

I understand now that it’s not that simple, but I refuse to give in to doomerism.

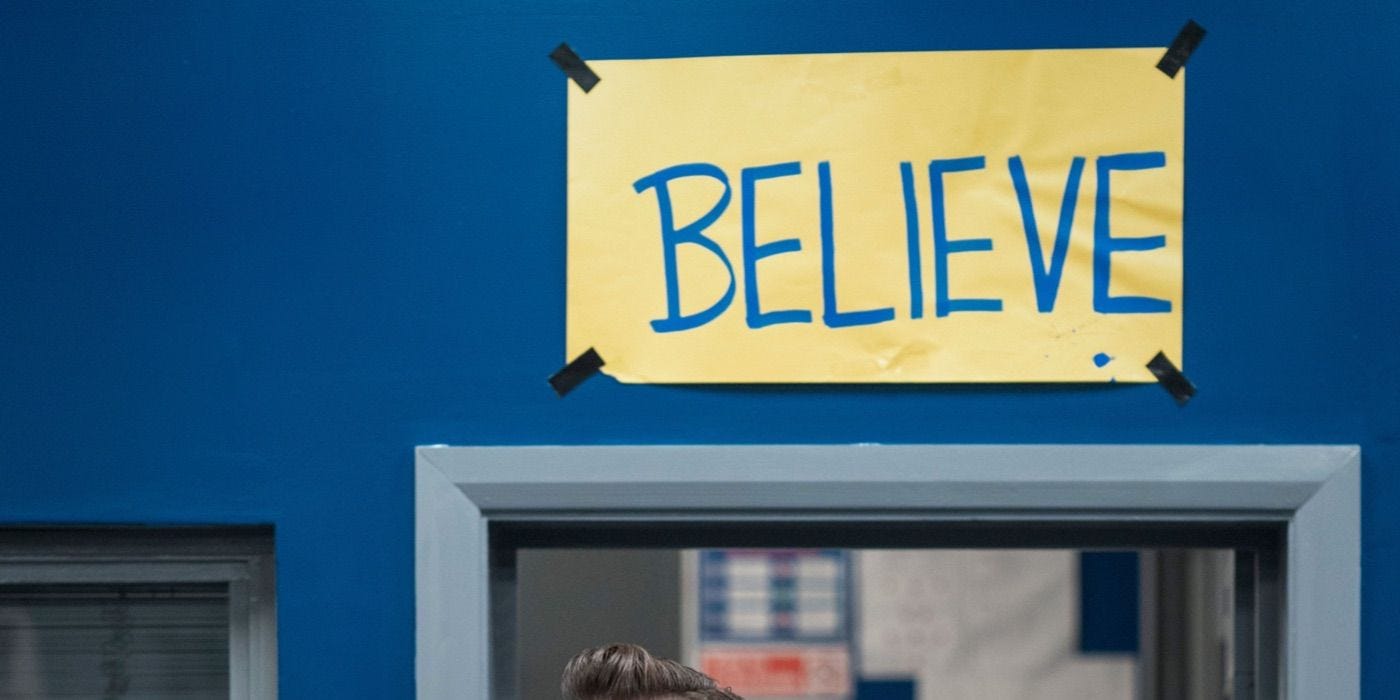

For months, my social media feeds have been saturated with people expecting the absolute worst, people taking on the role of Major League 2’s Johnny but with the fate of the world in place of a baseball game. I can’t really blame them—again, there’s plenty of reasons to feel bad about the state of the world—but I can’t join them, either. I see too much possibility—too many people fighting for a better world, too many people refusing to accept the status quo, too many people willing to learn and adapt and work hard—to believe that the bad guys are always going to win.

Progress isn’t guaranteed, and it sure as hell isn’t easy. It is possible, though.

The bad guys can lose, the tide can turn, and a better future is in our reach.

The first step is allowing yourself to believe.

—Scott Hines (@actioncookbook)

"Fuck those guys" can be an ethos.

My wife eloquently put the events of the last 24 hours as “it feels like Marty just grabbed the Grays Sports Almanac back from Biff”