When the statues come down, how will we remember our history?

That’s what they’re saying, the people who are very concerned about history. They’re clucking their tongues and shaking their heads sadly. Well, of course I don’t agree with what General Consternathan P. Hornswoggle did — it’s important to them that you know this, that the Civil War was just an unfortunate misunderstanding, you see, and it’s sad that that good man on that bronze horse somehow ended up on the side that he did — but after the war, he did build the first candy cane factory in this town, you know.

So it’s a complicated legacy.

There was a dot on the map for that statue, that statue of a man who sold people. Or maybe he didn’t sell people. Maybe he just fought tooth and nail for others to be able to sell people, or maybe he just believed it was noble for each subdivision of a nation to decide for themselves whether or not they agreed with people selling people. Either way, his dot just got moved. It’s in the middle of the river now, or a lake. Some people got together, hatched a plan, and that plan ended up with him and his horse at the bottom of some water. Years of serious and deliberate civic debate couldn’t get it done, so the people figured it out for themselves. The free market works.

Sad about the horse, but try not to find yourself welded to an asshole, I’ve always said.

Anyhow, the dot’s moved to the middle of the river and now some people, those serious guardians of tradition, they’re crying foul that we’re throwing away our history, that we’ll be doomed to repeat bad things — we agree they’re bad — if we don’t herald those bad things in bronze, put them in the middle of a roundabout and shine some lights up on them. Look how much we hate those things, how much we lovingly polish those things once a month. Oh, we agree these things are bad, but they sure give the place some charm, now, don’t they? Old-world charm. They had bad things in the old world and we’ve got ‘em too. Gotta keep ‘em up so we don’t forget how bad they are.

Now they’re gone, and we’re going to forget, aren’t we? Our beautiful dot isn’t on the map anymore. Google thought it was funny to let us leave it there for a couple of days, a dot in the middle of the river, but then they just took it off. Now it’s gone completely.

But look closer.

The lines are still there.

Every city’s got ‘em. The magic barriers, maybe they’re not labeled right there on the map as what they are, but everyone in town knows what they are. Might be a railroad track or a highway, or a six-lane street that you knew you weren’t supposed to cross, as though the city was a different place on the other side of the street.

Of course, it is different on the other side of that street. On one side the air is worse. There’s no grocery store, no bank branch or hardware store, but there is a rubber plant. It chokes the air. Makes people die younger. It was allowed to be built there, because it’s on the other side of the street from the people who paid for it.

The people who’ll get paid for it.

The street marks the line. It might’ve even been put there to help emphasize the line, a highway run right through a neighborhood through surely an unfortunate coincidence of midcentury planning, an S-curve that had to run right through that spot and no other. Sorry about the businesses that were there. Progress. That street was put there to mark the line, but the real line was on paper. You didn’t see that until later.

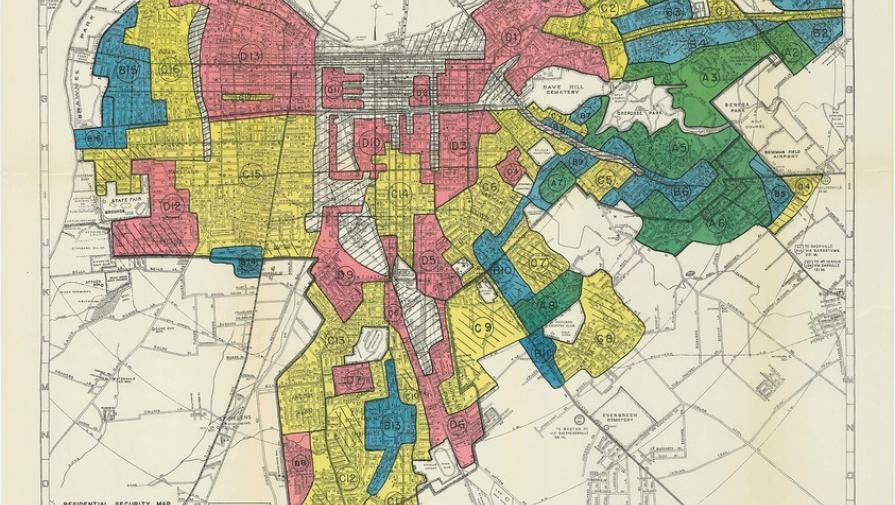

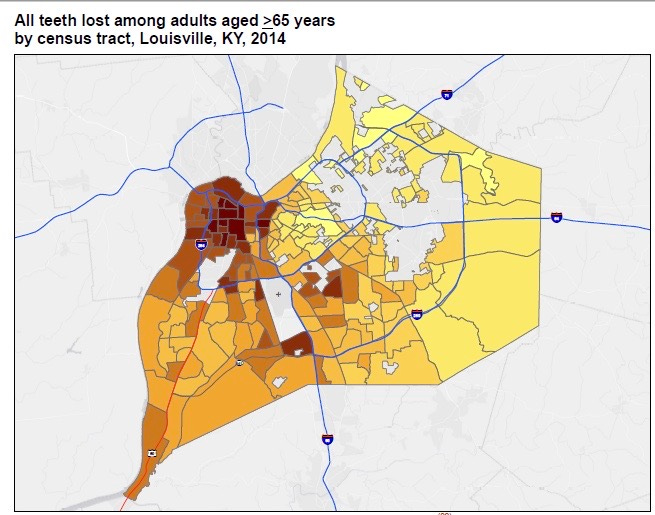

The lines on the paper made it real, made the difference set in. One side of the paper got mortgages, one side didn’t. Didn’t matter how short the commute was or how pretty the building stock, all the things that people might decide fifty years later to be valuable again, the lines said they weren’t valuable, so they weren’t.

But the street marks the line.

What if they come for the lines? They’re starting to worry. They took our dots, now they’re coming for our lines. That’s a great question. What if we tore down those barriers, knocked down that highway that happened to run down that line, fill it in with a park and some nice public art to say we’re sorry, reconnect the sides with a ceremony where we announce that we’ve reconnected and show off all the art that proves it.

How will people even know who they are if there isn’t a line to be East or West of?

Well, then we’ll have to look at the colors on the map. I don’t mean skin color, but of course it correlates — another coincidence, the guardians of history will insist — but what I really mean is the kind of colors on a map that tell you a story. That fancy kind of map, the kind that takes a research project to put together, the kind you tack up in the mayor’s office so you can frown at it and then call a committee together. You’ll all frown at the map in committee, and then the mayor’s gotta go entertain some guests from out of town. They’ve come to see our dots. (Other dots. Good dots.)

You can put all sorts of legends on that map, color in all sorts of things you want to know about a community. How many people own a home, and how many rent? How long do people live? How loud is it? How much money do people have in the bank? How far do people have to travel to buy fresh produce? How many of people are dying of this new disease? We’ll mark one in green, ‘cause those folks are good to go. We’ll mark the other in red, ‘cause I’d be angry if that was me.

Hell, look at that. We don’t even need the lines to see where the lines were drawn. The shading shows our history, don’t you see?

Here’s another map.

CLANK.

You hear that? Another hundred-year-old hunk of cheap bronze was just toppled to the pavement. Thought the noise would be heavier, but instead it sounded like a snow shovel hitting the ground. Turns out it wasn’t a glorious monument to history after all, it was just a cheap mass-produced totem of spite. Only put ‘em up when it got cheap enough to mail-order your hate.

Maybe they’ll all get thrown in the river, all the silent sentinels and complicated legacies. The fish can swim around our dime-store version of history, wonder what took this guy so long to end up down here, and wonder what the horse did.

If we really want to remember our history, we don’t need statues to tell us what happened, and most of them aren’t telling the truth anyhow. We could find the history in a book, but even that’s not necessary and it doesn’t seem like many people like being told to read books these days and lot of those history books aren’t totally honest either.

If we want to remember our history, we can look at our present and realize nothing got this way by accident. Nothing got this way because some people just like living that way. Our country and our cities didn’t stop being shaped when those bad men in bronze climbed down from their horses. The effects of what they did — and what generation after generation after them did — can be seen almost anywhere you look.

If we want to forget our history — if we want to be forgiven for our history — we’ve got a lot more than statues to tear down.

The statues are a good start, though.

CLANK.

— Scott Hines (@actioncookbook)

Never knew about the mass-produced statues. Linked article was an interesting read. Thank you.

One of your best. Though I do spare a thought for the horses.