There's still a swamp under there.

Considering Nippert Stadium's history and the season ahead.

A place I love was built on top of a swamp.

That’s a painfully obvious metaphor, but college football has always lent itself to those sort of things; subtlety has never had a great foothold in this world.

The swamp I’m talking about lies somewhere beneath one of the best college football stadiums—and thus one of the best stadiums, full stop—in the country, the University of Cincinnati’s Nippert Stadium.

While it may not have the capacity of some of the sport’s more well-known fields, it can go toe-to-toe with any of them on history. Depending on exactly how you measure these things—and again, unanimity on how things are measured is not a hallmark of the sport either—the 40,000-seat venue in the middle of UC’s Clifton campus is one of the five oldest stadiums in college football, having played host to games as a permanent structure since 1915.

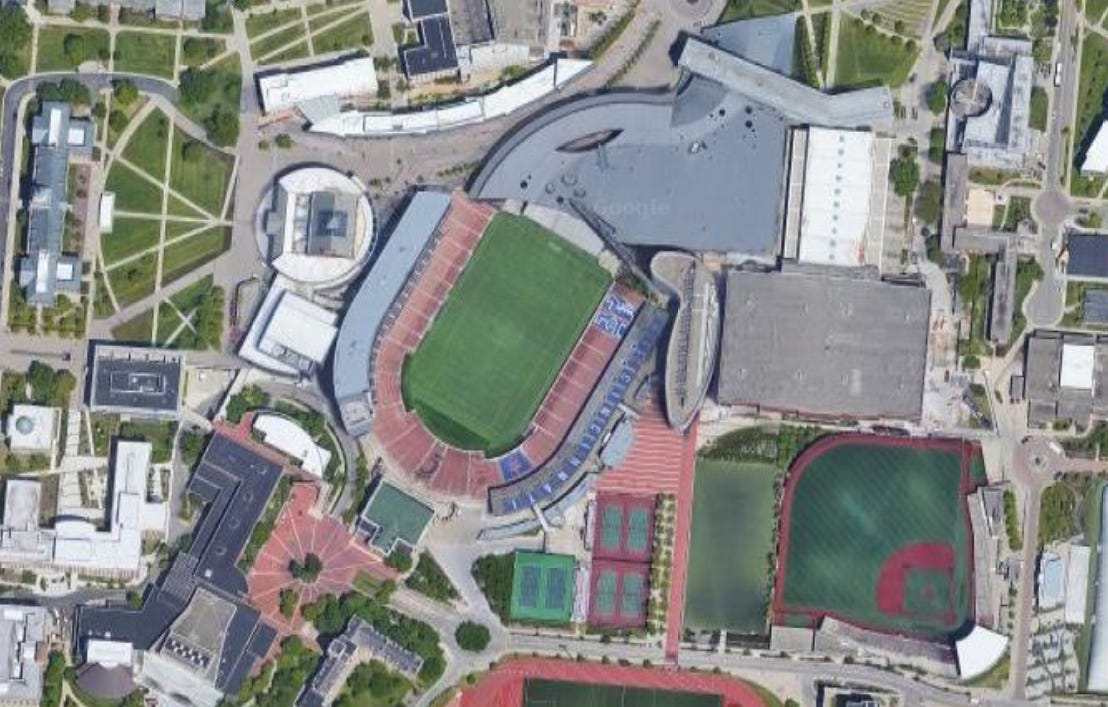

When I say in the middle, I mean it’s truly in the middle of campus, to a degree that can be hard to comprehend for someone who’s never stumbled into it. It’s caged by campus life on all sides, wedged with inches to spare between the student union, recreation center, athletics department offices and the vocal arts building. Where some schools have wide-open fields and ample tailgate lots surrounding their stadia, Cincinnati has the entire student experience peering over the grandstands.

Practically speaking, this means two things.

First, it’s loud. Despite a seating capacity on the bottom end of top-25 football programs—and yeah, the Bearcats enter this season ranked #8 in the Associated Press poll, the same place they finished in last year’s poll, did you think I was somehow not going to mention that?—a sold-out night game can roar as loud as almost anywhere in the country, a phenomenon that once led my friend Steven Godfrey to refer to it as a “baby Death Valley”, a fond comparison to Louisiana State’s cacophonous Tiger Stadium.

Second, it’s inextricably a part of campus. Where a less-football-inclined student 100 miles north at Ohio State could easily pass four years between matriculation and commencement without setting foot in the hulking Ohio Stadium, there’s simply no getting around Nippert. It’s on your way to class, and sometimes it’s just the shortest way to get there. Most days of the year? It’s wide open, with the gates open and even the field accessible to the general public as long as there isn’t a practice, a fact that recently stunned a friend visiting the campus. Occasionally during my time as a student there, after going for a run around the perimeter of campus, I’d finish with a stair run and a 100-yard sprint from end zone to end zone, simply because I could.

(One night I decided to time my own 40-yard-dash on the FieldTurf and that’s a humbling experience even as a 23-year-old who was in pretty good shape, let alone a [mumbles] who’s [mumbles]. But I digress.)

Of course, that centrality to the campus is why it’s there.

The stadium itself began its first phase of construction in 1915, but the concrete and steel was laid around a place where football was already being played, and that place was simply a marshy lagoon (what I’ve chosen to refer to as a “swamp” for rhetorical reasons) that was accessible to students because not much else could be built there. This is all laid out in an excellent and extensive history compiled by Spencer Tuckerman a few years ago for OhVarsity!, which I encourage you to read.

In 1915, that swamp gained the first foundations of what would become the stadium you see today, but it would take a tragedy to give it the name it now bears.

On Thanksgiving Day 1923, James Gamble Nippert, a 23-year-old center for the Bearcats, received a deep spike wound during a game against then-and-still-hated archrival Miami University. The game was played in a driving rain, and conditions were terrible—placing the stadium in a natural low point in the terrain made it easier to construct stands around the field, but harder to drain water away—and the wound’s severity went unnoticed until after the game, as it was quickly covered in mud. Nippert developed blood poisoning1, and passed away on Christmas Day, reportedly uttering “five more yards to gain, then drop” as his final words.2

Nippert’s family was heartbroken, and his grandfather—a Gamble of the local Proctor & Gamble fortune—paid for the stadium’s completion as a way to honor the young man. Carson Field was renamed, and a monument was placed in the south end zone in 1924, where it’s sat sentinel for nearly a century as everything changed around it.

Now, I’ll confess to some bias here in finding Nippert Stadium such a compelling place, because I’m both an architect and a two-time alumnus of the University of Cincinnati. That conflict of interest aside, though, I simply believe that college football stadiums offer far more interest to the viewer than professional stadiums do. The shiny, billion-dollar-baubles that municipalities fund for NFL franchises offer far more amenities, more features, and more sheen, but little more than a thin sense of bemused whimsy as a personal statement. A shiny new Roomba or a paperweight or a polygonated sphincter might look interesting on television or as you fly through town, but it’s got no story to tell beyond “the tax levy passed”.

In contrast, Nippert—like many other college fields—has grown in fits and starts over more than a century. A horseshoe extended, then completed. A second deck added, then extended. A press box built, then demolished, then built again, but bigger this time. This happens as a need arises or the money becomes available, surging as a program tries to build its way to respectability, and stalling when that respectability doesn’t come right away. It exists as any college campus should, as a living record, a place that allows every successive generation of graying alumni to periodically return and find parts they recognize and parts they don’t, a handy way of orienting one’s place along time’s ceaseless march onward.

Those box seats weren’t here when we were freshmen.

You used to be able to see the power plant smokestack from here.

I threw up over there.

That monument has looked out over a century-plus of football; some of it good, much of it wretched. The Bearcats have bounced from the Ohio Athletic Conference to the Buckeye Conference to the MAC, Missouri Valley, Conference USA, Big East and American Athletic, with long stretches of independent status scattered in between. In 1982 they were briefly booted from Division I, and there was a time where tearing Nippert down was briefly considered viable. This year it will look out over a team with legitimate playoff aspirations, something that shows just how long the twenty-one years since I first sat in the bleachers during freshman orientation have really been.

College football has grown in much the same way as those stadiums, evolving from a distant time where the concept of “student-athletes” wasn’t a laughable tax dodge to a massive business whose hefty profit imperatives drive everything, from craven conference realignments and their respondent Alliances to an entire season blithely played through the worst of a pandemic.3

Some things change, but others don’t; young men still get injured and even die in the service of college football, their stories differing from Nippert’s in the color palette and resolution with which we picture them but not the fundamental senselessness of their deaths. The stadiums add tiers and sponsors and glittering amenities for deep-pocketed boosters and corporate partners, but there’s still a swamp underneath it all.

The literal swamp—lagoon, marsh, whatever—underneath the stadium that bears his name may well have contributed to James Gamble Nippert’s untimely death. That swamp also made possible something that outlived even his luckiest classmates.

A useless, brackish place, available because it wasn’t suitable for building anything else, became a place where students could run around a toss a ball between classes. That gave it meaning, and that meaning gave it utility, and that utility led to history. All over the country, useless places just like it filled in over the course of a century and a half to make something that’s often ugly, stagnant, filthy and even dangerous, but filled with moments of beauty and joy and hope that this is finally our year.

Ninety-eight years after James Gamble Nippert’s death, people will gather on that spot once again this Saturday, because there are still scores to settle4, still traditions to uphold, and still things worth loving there, even if we know full well what lies underneath.

—Scott Hines

“The complete story behind the name of the University of Cincinnati's historic football stadium”, UC Magazine, April 2013

I was on the record as being deeply uncomfortable with last season, which felt like it laid bare the worst motivations of everyone involved in the sport besides the players themselves. The sport is still a long way from perfection, but vaccines and NIL rule changes have done wonders for restoring my enthusiasm this year.

The Cincinnati Bearcats’ win against Miami on Thanksgiving Day 1923 brought the all-time record in the rivalry to 14-12-1 in favor of Miami. The Bearcats drew even in 1953, at 26-26-6; Miami has led in the series ever since. As of today, that record stands at 59-58-7 Miami, on the heels of a 14-game winning streak by Cincinnati. On Saturday, they can pull even again for the first time in 68 years, and that matters, to me.

I had no idea about any of this. Fascinating.

You know, as a proud Miamian and thus lifelong hater of anything to do with the University of Cincinnati, I’m trying to find a reason to mock this. But I can’t. Here’s to college football—and a big RedHawks upset this weekend.