This post originally appeared on Every Day Should Be Saturday, which was a good website.

You know when you get old in life, things get taken from you. That’s, that’s part of life. But you only learn that when you start losing stuff. You find out that life is just a game of inches. So is football. Because in either game — life or football — the margin for error is so small. I mean, one half step too late or too early you don’t quite make it. One half second too slow or too fast and you don’t quite catch it. The inches we need are everywhere around us. They are in every break of the game, every minute, every second.

— Al Pacino (as Tony D’Amato), Any Given Sunday

To me, the most wonderful thing about college football — the thing that elevates it above all the other lesser sports — is its merciless clarity. There are no second acts in college football (unless you’re 2011 Alabama). Maybe the sport’s never been great about setting clear ground rules, but it’s incredibly good at letting you know exactly where things went wrong. The vastness of the field of opposition and the brevity of the schedule, even in the playoff era, mean that more than most sports, one game — one play — can cost you everything.

The 2002 Ohio State Buckeyes know this.

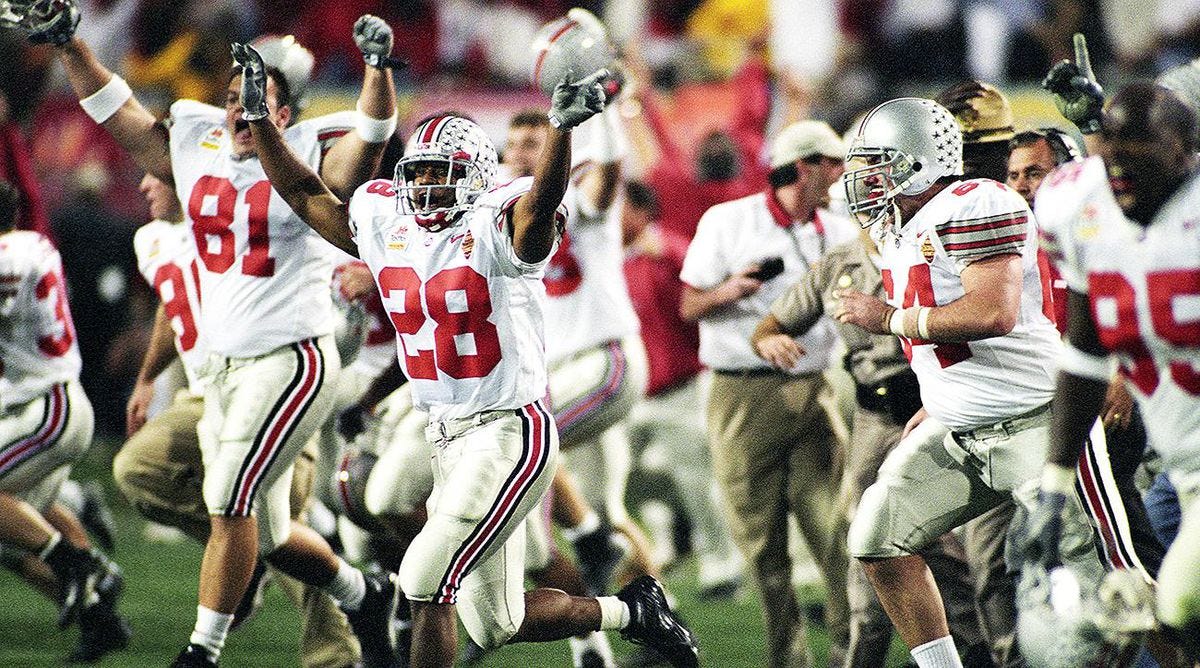

Dispute the overtime pass-interference call against Miami all you want (it was a good call), but never forget that the Buckeyes that year were simply one of the luckiest teams to ever win a national title. This is not to claim they weren’t good enough to win one; they were exceptional, loaded with NFL talent, bolstered by a shooting star in the backfield and a stifling defense.

Rather, this was a team that put themselves in position to lose many times—in a season where one loss assuredly would’ve kept them out—and yet they held on to become the first team in history to win 14 games in a season. A Chris Gamble interception against Penn State. A fourth down prayer against Kyle Orton’s Purdue. Overtime against Illinois. And a fourth-quarter comeback against the specter of an unthinkable indignity: losing a road game in the state of Ohio.

On September 21st, 2002, the Cincinnati Bearcats came within two dropped passes of beating the Ohio State Buckeyes for the first time in their modern history.

The night before, I probably should have died.

We’ll come back to that.

You have to understand what it’s like to root for a ‘little brother’ school. I don’t have anything against the Ohio State University. I attended high school in suburban Columbus. My older brother and many of my closest friends attended the school; I spent so much time hanging out on that campus during college that one friend actually thought I was a student there until years later. I halfheartedly root for their success most of the time, and full-throatedly root for them when they’re playing Michigan. There are just some things we do when we’re born in a state—things that come preset out of the box and persist because we’re too lazy to dig out the manual to figure out how to turn them off. It’s like motion-smoothing on a TV: it doesn’t look good, but I don’t know how to fix it. O-H.

I didn’t attend the Ohio State University, though. I attended the University of Cincinnati, and that’s where I truly grew up. It’s where I forged some of my longest-lasting friendships, where I learned to live on my own, it’s where I learned to shotgun a beer and design a building. (Not in that order.) (Sometimes in that order. Have you seen our architecture school building?) It’s a place that will be forever dear in my heart, even as the campus and surrounding neighborhoods become almost unrecognizable with change and the people walking across it look more and more like children every time I return.

When started attending school there in 2000, the University of Cincinnati was still firmly a basketball school in the public consciousness. The Bearcats’ men’s team had looked poised to threaten for a national title the previous season, had Kenyon Martin’s leg not snapped. The football team, meanwhile, was three years removed from their first bowl appearance in nearly a half-century and were still finding their way in Conference USA after decades of fruitless independent play. They’d make, and lose, two Motor City Bowls in my first two years on campus.

In the fall of 2002, a rare opportunity arose. They were coming to us! For the first time since 1900, when the Buckeyes were hardly a glimmer of an idea of the program they would grow to be, Ohio State would play at Cincinnati. Sure, it wouldn’t be at Nippert Stadium; the historic on-campus jewel of a stadium would be far too small to accommodate the crowd for that kind of game. It would be played at Paul Brown Stadium downtown, home of the NFL’s Bengals. And sure, at least half the crowd would be Buckeyes fans making the 90-minute trek south on I-71. Still, we got to be the home team. They were playing on our (borrowed) turf.

The University of Cincinnati football team that year wasn’t yet the fiesty mid-major power it would become in the next decade under coaches like Mark Dantonio and Brian Kelly, but there was cause for a renewed spike in attention to the program, and much of that centered on sophomore quarterback Gino Guidugli. Guidugli, a top prospect coming out of Fort Thomas, Kentucky, just across the river from Cincinnati, had originally committed to play for the University of Kentucky.

He would be the next dominant arm in Hal Mumme’s high-flying Air Raid offense, the same offense that had turned Tim Couch into a #1 overall draft pick several years prior. Just before National Signing Day, though, Mumme was fired under a cloud of NCAA recruiting violations, and Guidugli reconsidered his future with the Wildcats. He ended up staying even closer to home, and immediately began lighting up scoreboards for the Bearcats. He threw for 2,500 yards in his freshman campaign in 2001 and looked poised to do even bigger things in 2002.

The Buckeyes, meanwhile, never struggled for recruits, but were in a transitional era of their own in the 2002 season. Though it might be hard to remember now, given the success the program has had the last two decades, the ‘90s were a period of intense frustration and missed opportunities for Ohio State. In the John Cooper era, massively talented teams managed to fall short every year—usually at the hands of Michigan. Cooper’s 2-10-1 record against the Wolverines would be the ultimate albatross on his otherwise decorated career, and it would chase him out of Columbus in favor of a relatively-unknown coach who’d been quietly winning FCS titles at Youngstown State.

It might not be evident from the record books—in Cooper’s last season, the Buckeyes went 8-4 with an Outback Bowl loss to South Carolina, and in Tressel’s first season, they went 7-5 with an Outback Bowl loss to South Carolina—but to anyone who witnessed it firsthand, the energy around the program had completely changed.

Much of this could be attributed to an arrogant boast that was delivered on.

In one of his first acts as Ohio State’s head coach, Tressel, addressing a home basketball crowd, had told fans “I assure you that you will be proud of our young people, in the classroom, in the community, and most-especially,”—he paused for maximum effect—“in 310 days in Ann Arbor, Michigan, on the football field.” Fans realized he understood the importance of the rivalry, and when he delivered on that promise with a 26-20 win in Ann Arbor that fall—only the third Buckeye win in 16 years in the rivalry, and their first in 14 years at The Big House—he was already on his way to becoming a legend.

The 2001 season was only the beginning for his team, though.

Coming into the Ohio State-Cincinnati game, there was little to suggest that it was going to be a close contest. The Buckeyes had rolled to three easy wins already, blowing out Texas Tech and Kent State, and easily dispatching #10 Washington State in a College GameDay matchup. The Buckeyes’ early success was driven in no small part by the incredible running of true freshman tailback Maurice Clarett, who had 517 total yards and seven touchdowns in his first three collegiate games.

Their fourth game of the season would be a virtual home game against a team that had barely eked by pre-BCS-quality TCU and lost to West Virginia. In their last meeting, a 1999 game in Ohio Stadium, the Bearcats had staked a first-half lead only to watch the Buckeyes cruise in the second half to a 34-20 victory whose momentary closeness seemed indicative more of boredom on Ohio State’s part than anything.

I attended that 1999 game, a lone idiot cheering for the Bearcats’ early scores from C Deck, and I wasn’t going to miss this one.

With Clarett on the sidelines recovering from minor knee surgery, the Buckeyes were down a major weapon in their run-heavy attack. Lydell Ross stepped into the role and hardly missed a beat, though, racking up 130 yards on 23 carries. The Bearcats struck first, with DeMarco McCleskey taking an option pitch from Guidugli for a first-quarter touchdown. School-record-setting and Lou Groza Award-winning kicker Jonathan Ruffin missed the extra point (something that would prove important later), but a field goal later would give UC a 9-0 lead at the end of the first quarter. He added a career-best 49-yarder to keep the lead at 12-7 by halftime. The Buckeyes were sleepy, perhaps, but surely any reasonable person among the Cincinnati-record 66,319 fans in attendance expected them to pull away in the second half, just as they had three years earlier.

I wasn’t one of them.

As a UC student, I’d had access to tickets, so I requested them for myself and one of my best friends from high school, an Ohio State student. He was driving down from Columbus, and I planned to drive up the night before from Nashville, where I’d just moved into temporary housing in anticipation of starting an internship that Monday. The forecast called for sporadic heavy thunderstorms, but if there’s anything that’s ever registered with a 19-year-old man, it’s not changing your plans on account of some conceptual risk.

Somewhere just south of Elizabethtown, Kentucky, there’s a broad, flat stretch of I-65 with a wide grassy median. I think there’s cable barriers now, but at the time, there wasn’t anything but grass between the northbound and southbound lanes of the interstate. Around 9 or 10pm that Friday night, I was cruising north in the steady rain, making good time on my way back to Cincinnati, on my way to see the ‘Cats upset the Buckeyes.

People always talk about your life flashing before your eyes in a near-death experience, and maybe that’s true for some people, but I didn’t have time for that. I saw something, and all I had time to think (or say?) was “Oh, SHI-” as a big black Ford F-150 heading southbound lost control, fishtailed across that grassy median, and found itself facing west and heading east in my northbound lane. My little two-door Pontiac Grand Am hit the driver’s side door head-on at 70 mph. There was no drama, no time to lament my lost loves or that novel I never wrote, just a half-second of “oh, that CAN’T be good”, an incredibly loud noise, and then nothing.

If you’re old enough to remember when air-bags were a new feature and not standard equipment on every car, you might remember car commercials with super-slow-motion video of them fluttering out as they deploy, pillowy and white as a cloud, looking for all the world like a nice place to take a quick nap while your car crumples. The reality is more like a ten-pound bag of potatoes being launched at your face from a cannon, but I suppose it’s better than the windshield or the steering column. For a few interminable seconds after, I had a fleeting but wholly serious internal debate of “am I dead?” I’ve never been confident the afterlife or what it might entail, but for a brief moment in a crumbled, smoking wreckage of a low-end sports coupe on the side of a Kentucky highway, I wondered if that might be all it is.

In the second half that I never saw, the Bearcats tried to keep the inevitable at bay. Guidugli threw 52 passes, completing 26 for 324 yards and a touchdown. Ohio State took the lead shortly after the half; Cincinnati took it back. It was only with just under four minutes remaining, when quarterback Craig Krenzel scored on a keeper, that the Buckeyes led by more than a field goal. 23-19.

The Bearcats had one more drive to try to take down the big one, to dominate the state if only for a day. That first-quarter missed XP loomed large, as they’d need a touchdown now. Guidugli drove them the length of the field, getting to the Ohio State 15 with a minute remaining. First down, Guidugli finds senior wideout John Olinger open in the corner of the end zone—and he drops it. Second down, an incomplete pass. Third down, George Murray, a sophomore backup QB in at receiver, stretches on a fade route in the opposite corner, appears to pull it in, snatching the victory, and… he doesn’t pull it in.

Guidugli’s final, last-chance heave is tipped and picked, and the Buckeyes escape back north with their perfect season intact. They’d have their other scares in that dream season, but they’d escape them all unscathed, the first 14-0 team in major college football history. Jim Tressel becomes a Columbus legend, the kind a middling compliance scandal over tattoos could never take away. The Bearcats go 7-7, and head coach Rick Minter gets one more season before the administration decides to spruce the place up on their way into the Big East, hiring away Ohio State’s defensive coordinator, Mark Dantonio. By the end of the decade the Bearcats would be playing in BCS bowls and challenging for titles themselves.

A few inches here, a few inches there.

Upon examining my car a few days later, the insurance adjuster called my dad to confirm the details of the police report, because “it says no one died, and that doesn’t match the car I’m looking at”. I hit a three-ton truck head-on at highway speeds and walked away with nothing but nine stitches in my forehead and a prescription for Vicodin that I threw out because it made me sick. The other driver, who’d apparently been sleepy after a long shift at the nearby UPS sort facility, was taken by helicopter to Louisville. A few days later all the hospital would tell me, a stranger on the phone, was that “that person is currently a patient here”, the first four words of which were a tremendous relief and a mild surprise.

An inch or two to the left or right, and the Buckeyes are never champions. An inch or two to the left or right, I don’t get to find out about that or anything else. I don’t get to know how that story ends. I don’t call my friend the following morning, apologizing that we were going to miss the game, only to have him interrupt, completely unconcerned about the game, and ask if I needed a ride from where I was, five hours away. I don’t get reminded what true friendship was really about.

It’s hard to explain to people who don’t appreciate sports why you do. For me, among other things, it’s that it gives us moments of clarity without having to face life and death moments like this. We don’t always see where things go right or wrong in our live. Missed opportunities can go unseen for years or forever. Mistakes can take years to play out. We might never know what might have been because the possibilities are too complex, too interdependent, too subjective to know. A ball dropping through the outstretched hands of a receiver is unambiguous. He catches it, we win. He drops it, they win. This isn’t about those players, and this isn’t about blame. It’s just a simple fact. Things could’ve played out very differently.

I’ve got plenty of ambiguities in my own life. I know I’ve missed opportunities. I know I’ve made mistakes, personal and professional. We all do, but knowing that doesn’t keep me from staring at the ceiling thinking about them some nights. Did I say something wrong? Could I have seized on a chance that I didn’t? What would life be like if I’d taken that job, or handled that relationship differently, or eaten that gas station sushi? How could it all have happened differently?

I’ve got a nice life. I’m blessed with a wonderful partner, two beautiful children and a perfectly acceptable dog. I’ve been lucky. A couple inches are all that kept that from not happening.

Sometimes you just need a moment of clarity to remind you.

—Scott Hines (@actioncookbook)