Social media today contains innumerable and varied subcultures—some vibrant, some toxic, some truly bizarre—but there’s one that I’ve come to enjoy in a perverse, ironic fashion of late, and that’s the social media world of Hustle Culture.

That’s not a proper name, per se, but rather an idea, one that could be referred to a bunch of different ways—LLC Twitter, Success Instagram, Business Brain Facebook, LinkedIn—but they all describe a certain kind of person: They’re excited about business, but not necessarily a particular business of their own. They’re excited about the idea of business—the Successories-inflected jargon, the rise-and-grind-and-increase-shareholder-value energy, the apocryphal legends of billion-dollar businesses founded in garages with a dollar and a dream, the obviously-fake stories of job interviews gone magically right or terribly wrong, the steadfast and completely empty faith in an undefined notion of “innovation”—these people just freaking love business.

Every few months, some golden nugget of Business Think from this world will wash ashore on the riverbank of Relatively Normal Person internet, often in the form of a ludicrous either-or.

Would you rather have 10 million dollars, or a great business idea?

Would you rather have 20 million dollars, or an 800 credit score?

Would you rather be financially secure for your great-grandchildren's lifetimes, or ride in an elevator with Warren Buffett?

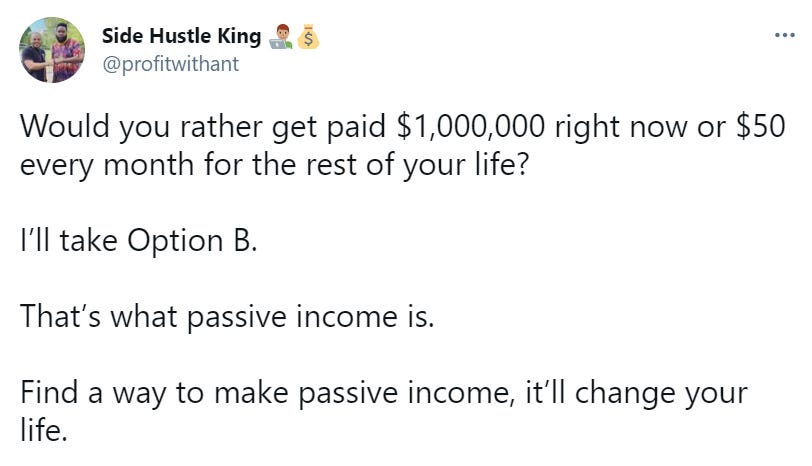

I find these propositions utterly delightful in their earnest wrongness, and the genre may have reached its apotheosis with this magical and math-challenged tweet that went viral last week.

For the record, you would have to live 1,666 years for Option B to be a break-even proposition, and that’s without factoring in the time value of money, the magic of compound interest, or the likelihood that you will not live 1,666 years. To his credit, the man who tweeted it eventually admitted that his math was flawed, but seemed to relish the discussion nonetheless, and even found defenders amidst the deserved opprobrium.

People in this mindset—who, to be fair, I’m not even sure are actually real so much as they are the inevitable ghosts in the system of capitalism, bad lines of code in a simulation, the rival Tron cyclist to all of us trying to just live a normal life—are prepossessed of the notion that there is simply nothing better in life than to be Good At Business and Known As Such.

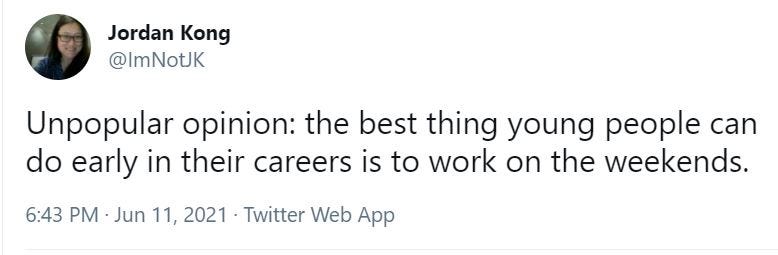

Of course, they’re fun to laugh at until they unwittingly expose the toxicity that underpins much of this mindset, and that’s where another recent tweet comes in, one that I’ve been vaguely mad about for a week and a half:

I get that there’s a certain fun that comes with viewing yourself as controversial online—I publicly defend Cincinnati Chili often for just this reason—but if you truly feel like you have to preface a public statement with the caveat that it will be unpopular, it’s worth taking a moment to reflect on the fact that you might just be wrong.

This tweet, like the other, received an appropriate amount of blowback—which is to say, a lot—but I’d still like to address it myself, both on a conceptual level and a personal one.

Conceptually? It’s trash.

It’s predicated on the notion that companies should be abusing the time of their workers, intentionally and structurally understaffing such that a significant, valuable portion of their output depends on (usually) younger workers vastly exceeding a 40-hour work week, eschewing a personal life or leisure time, running themselves absolutely ragged for no equity stake or additional compensation aside from the fleeting hope that someone will notice how hard they are working and reward them by giving them more work.

Now, practically: do I understand that this tweet exists because this is, in fact, how many industries work?

I do! It’s still trash.

Early in my career—and by this, I mean my non-writing career, which is as an architect—I fell for exactly the kind of logic this person is espousing. After graduate school, I got my foot in the door with a large, prestigious firm with many high-profile projects, a place I was deeply excited to tell people that I worked at. I was going somewhere. From day one on the job, I was working overtime, and I didn’t complain, because that was the expectation going in. I rarely had a weekly timesheet finish below 55 hours, and the norm was closer to 80. In once especially-frantic week, I logged 102 hours in the office out of 168, and it might’ve been even more had the project team not taken a single evening away from the office to all get absolutely blinding drunk.

At the time, I shared a small apartment with a college friend in a similar situation at a similarly prestigious firm, and we literally went months at a time without seeing each other awake, which I suppose is one way to back into an ideal roommate scenario. I wasn’t happy, but I was also doing exactly what I’d set out to do—working on legitimate skyscrapers, with extremely wealthy and influential people as our clients.

I was in the room where it happens, if only standing in the back.

One late night, I recall looking at my supervisor, a miserable man roughly my own age now, and briefly thinking “my god, I do not want to be living this life at his age”, perhaps the only lucid thought I had during those long, sleep-deprived days, and one that quickly escaped me as I went back to editing another rendering before the next Extremely Important Deadline, which in retrospect was not especially important.

The day I was laid off—in a conference room with thirty other people receiving termination paperwork identical to my own, one month to the day after Lehman Brothers collapsed and the market for our particular brand of luxury-good design cratered—I wasn’t upset. I wasn’t mad that my hard work had not been rewarded, or that all those late nights were for naught.

I was relieved that I got to go home and sleep, because I was just so, so tired.

Now, I don’t think this experience is especially unique; I would imagine that many of the people reading this have gone through similarly taxing stretches in their own careers, and I don’t really think the readership here skews much toward the “young people” demographic referenced above, either.

That said, I’d like to pretend for a moment that that’s who I’m addressing, and offer some counter-advice of my own, a How To Succeed In Business If That’s What You’re Out To Do.

Do not trust anyone who talks about paying your dues.

Unless they’re talking about union dues, they do not have your best interests in mind. They are trying to justify their own past mistreatment as an essential and edifying experience and not simply a time where they lacked power. This is true well beyond the narrow purview of business, but it’s especially true here.

Watch, and listen.

This is the closest I will come to granular, tactical, old man advice: pay attention. I have worked in healthy office cultures and unhealthy ones, and it can be hard as a young worker to recognize which is which, but it’s a lot harder with headphones in.

Listen to what people are saying, because when you’re at the beginning of your career, there are a lot of things won’t be explained to you; you’ll have to see and hear for yourself. Listen to how people interact, and how others are treated. If it sounds unhealthy, it probably is.

Take care of yourself.

This works on several levels.

First, literally, take care of yourself. A job that requires losing sleep, eschewing exercise, leisure, relationships, family time, a job that finds you eating takeout in front of a computer screen every night and abusing alcohol or drugs to cope—it is not going to further your career. It is going to lead to burnout, personal collapse, or worse.

But on a secondary level? Consider your priorities first and foremost. This might be selfish millennial thinking, but it’s absolutely true. You are only important to an employer inasmuch as you impact their bottom line, and that understanding should be mutual. Do not accept promises of advancement or talk of “family” unless they’re the rhetorical frosting on top of fair compensation and actual development.

Understand who HR works for.

I apologize in advance if anyone reading this is a Human Resources professional who is good at their job; I understand that many are good and ethical people.

[Stephen A. Smith voice] HOWEVER.

As addressed in the previous heading; take care of yourself. A Human Resources department does not exist to protect workers; it exists to protect the company. Sometimes these interests overlap, but often times they do not. Understand that—regardless of what should be true—anything you say to them may quickly be repeated back to the person you’ve talked to them about.

Again: take care of yourself.

Run a race that goes somewhere you actually want to go.

I often think back to that supervisor, toiling away his early middle-age, saying goodnight to his children over the phone each night, and I am deeply grateful that I did not stay on the road to that place.

Look around the office, if you indeed are in an office once again: the middle managers, the people whose position you might work your way into in ten or fifteen years—do they look miserable? Are they living a life that you want to be living? If the answer is no, you need to start looking for a different direction to run in, and fast.

Do better, and break the cycle.

In time, young workers become not-so-young workers; in many cases, they become the ones overseeing the young workers they once were. Take that opportunity to change things.

Business is business, but unless you’re among the truly deranged Commerce Fans I started out talking about today, business is just a means to an end: a comfortable existence, a good life, doing something you can be proud of or simply going home to the ones you love at the end of the day.

Businesses can be built that operate this way, and they can be successful.

Ignore any advice that suggests otherwise.

—Scott Hines (@actioncookbook)

What’s your career advice for young people?

This is all wonderful stuff. Especially your points about HR (I'm a 42 year old dude who has literally never worked for a company with a competent HR staff) and running the race you want to win.

The first piece of advice I have for young people is kind of a corollary to that second point, something I had to learn hard for myself a couple times before getting my career on track:

Sometimes it's the job that's bad.

It's not you. It's not your chosen career. It's where you've chosen to work. And while that sucks, it is correctable. It's easier to move sideways into a better job in your current career path than the blow it all up and start from scratch, so if you find yourself thinking very early in your career that you've made a horrible mistake and you need to get out, it can often* be a lot better idea for you to give it one more shot with a different employer in a slightly different position and see how the change of scenery suits you. Misguided career counselors may warn against job-hopping, but employers don't care unless it's, like, 3 jobs in a year with no plausible explanation.

The second piece of advice I have is to avoid job situations where people's passion for the trappings of the job blind them to the realities of the job. Video games (especially AAA studios). Sports-adjacent industries (*cough* blogging nation of the sporting kind *cough*). Any industry where there's a wave of naïve kids in their early 20s graduating every year that the industry can chew up and spit out. Companies will absolutely take advantage of the demand for their jobs and use it as leverage to keep down your compensation and use it as an excuse to ignore bad working conditions.

As you know, I spent part of the past week hanging out with my dad. At 69 years old, he's finally starting to look towards a future that doesn't include all-consuming work. He's quietly left most of the many boards and nonprofits he's been involved with, no longer attends industry conferences, and has receded into the background of his company (spending most of his time now working to sell it, actually, but shhhhh).

So this week, it was interesting to catch him in a much more relaxed and introspective mood than I'm used to seeing from him. Over dinner my last night in FL, I started to ask him about his career and how he went from being a CPA to an expert on dementia care over the past 30+ years. I watched it happen in real time, of course, but he was too busy and scarce to really give me any context at the time and I was far too young to understand anyways.

Talking about his greatest successes, prides and also failures, I more-or-less tactfully asked him why he was so driven by his work all these years at the expense of his family, his marriage, watching his kids grow up, and any of the other many things that have hurt and angered me over the years (we have a wonderful relationship now but it's taken my entire adult life to get to that point). And you know what the answer was? He wanted his face on the front page of the Wall Street Journal. THAT would mean that he made it. THAT was his measure of a good career. He kinda ruefully snorted as he said it because now, finally, he realizes how ridiculous it sounds. He never made it, either. He *almost* made it, supposedly, but his crosstown business rival made it and he never did.

This is going to probably haunt me for the rest of my life. I feel bad for him that he never quite made it, despite all his many business successes. But mostly I feel sorry for him, that he was so blinded by this for so long that I don't think he'll ever really understand how much of life he missed out on. Even now as someone who's made massive strides towards being a good dad, friend, and grandpa, he'll never know how much he missed while chasing that weird, singular metric.