Organized sports in 2020 were never going to be normal, but at some point in the last two or three weeks, things have gone from “this is a bad idea, but for the moment it is working” to “oh no nope this was always a bad idea and it is not working at all.” College football games are being cancelled left and right, to the extent that we might well end up with Northwestern and Indiana playing for a Big Ten title, the kind of thing that should only happen in the seventh season of a video game simulation. Where once games were scheduled fifteen years in advance, now schedules are being written on the fly with the equivalent of a “you up?” text sent from one’s doorstep.

The NFL, for its part, had been having marginally more success in holding the line against outbreaks, given the advantage of its athletes being well-paid professionals and not 21-year-old students living on college campuses. Even that relative luck has run out now, though, with multiple teams losing key players and the Baltimore Ravens organization essentially becoming a super-spreader event all their own.

I have had quite a bit of trouble taking any joy in sports this season, both because of problems like these and the greater context in which they’re happening. But I’ve found a silver lining, something to appreciate amidst the slow-rolling disasters. I’m enjoying the games that force us to acknowledge just how screwed up everything really is right now by showing us something that just wouldn’t have been possible in another season.

To wit: yesterday, the Denver Broncos played a game without a quarterback.

The Broncos found themselves in this predicament after determining that starting quarterback Drew Lock and backups Brett Rypien and Blake Bortles had all been exposed to backup Jeff Driskel, who tested positive for coronavirus. The team’s quarterbacks room had apparently not followed proper masking or distancing protocols, but at the very least they did not attempt to start a player who had potentially been exposed. That’s something, and in 2020 we can faintly praise any organization that does anything better than the worst possible thing that they can do.

But it left the team scrambling.

Social media quickly lit up with frantic discussion of who might step in. Blackballed social activist and former 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick? (No, the league doesn’t give up blackballing that easily, and he couldn’t have cleared quarantine protocols in time even if they would.) Former Broncos quarterback Tim Tebow? (No, he’s too busy selling button-down workout shirts.) Broncos offensive quality control coach Rob Calabrese? (No, the league objected to crossover between coaching staffs and active rosters.) Air Bud? (No, he’s been dead for years.) Some kind of super-intelligent football robot? (No: like patio heaters and Pelotons, they’re backordered right now.)

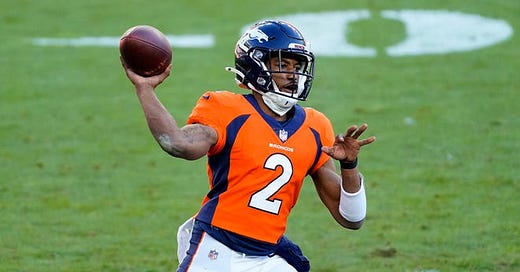

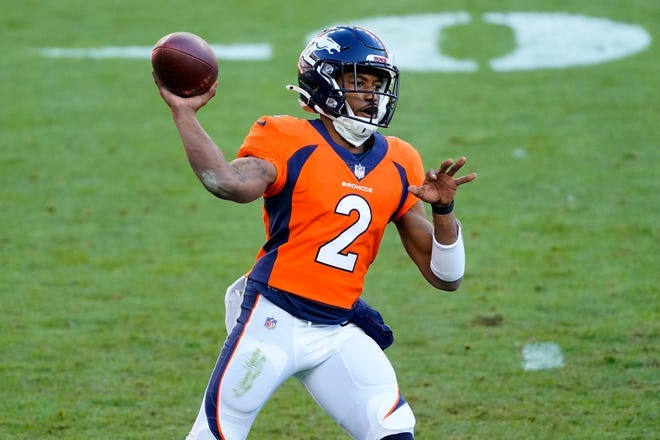

Eventually, the team landed on Kendall Hinton, a 23-year-old wide receiver signed off the practice squad who hadn’t taken a snap at quarterback since college at Wake Forest. This amused many, and set staggeringly low expectations from fans and sports books alike for the team’s performance on Sunday, expectations that they managed to still underwhelm in a 31-3 loss to New Orleans.

Hinton threw a total of nine passes, two of which were intercepted and only one of which ended up in the hands of a teammate, for a total of 13 yards passing. The game would have been one of only sixty-nine times in NFL history that a quarterback achieved a passer rating of 0.0, save for the fact that Hinton did not attempt enough passes (10) for his performance to be officially counted in that way.

Hinton will likely be back off the roster by next week or the week after, assuming that Lock, Driskel, Rypien and Bortles are cleared to play. He may go down as a Moonlight Graham or a Rudy Ruettiger—a footnote, an oddity, someone whose entire playing career comes down to a single fruitless appearance.

We shouldn’t hold that against him, or treat this moment as a failure.

Despite ample evidence in every single game, we often fail to appreciate how good professional athletes are at what they do. Every so often, a question will rattle around social media to the effect of “if you got 100 targets against a NFL defensive back, how many touchdowns would you score?” or “if you got a full season worth of plate appearances in Major League Baseball, what would your batting average be?” and there’s invariably a cavalcade of dudes who reply with “yeah I’d score a couple TDs and bat .278”, but of course they’re dead wrong. Unless you’re a former professional athlete or top-flight collegian yourself, the honest answer to these questions is “you would do nothing and actually die trying well before you got to the end of this hypothetical.”

The worst player on the field in any professional game is likely the greatest player his or her hometown has ever seen. There’s a sign on the outskirts of town that says “Welcome to [town], home of [player]” and there are a few doctors or accountants or shipping managers in that town who still lie awake some nights staring at the ceiling, thinking about how their own dreams of athletic glory were ended by that person.

It is a remarkable achievement to ever step on a professional field of play, regardless of the circumstances that placed one there. It may have taken a worldwide pandemic and four quarterbacks too stupid to wear masks around each other for the final step to be taken, but prior to that there was a lifetime of competition, of practice, of early mornings in the weight room and late nights of film study.

A professional athlete doesn’t need my sympathy, and he’s not even exactly the point I’m getting at today. In a year when everything is falling apart around us, we cannot allow any of our victories to be qualified. We survive our own memories only with careful editing; we take a mental image and crop it until the worst is just out of frame and retouch what’s left until it looks like something we can live with.

Take the wins and leave the rest.

Kendall Hinton was the pride of Southern High School in Durham, North Carolina. He led his team to a state championship in his junior season, and went on to a successful four-year playing career at Wake Forest. On November 29th, 2020, he took the field as a starting quarterback for a regular-season game between NFL teams, something only the tiniest fraction of athletes can ever dream of achieving.

How he got there is just the details, and when we talk about 2020 someday, we can leave plenty of details out.

—Scott Hines (@actioncookbook)

Even if I had read nothing else but the words "button up dress shirts", this would've been worth the read. As it was, I enjoyed the rest a lot, too.

My Dad, now in his 80s, likes to tell a story about when he was about 12 and still pitching little league. One year he had gone to the All-Star game, and that summer he was out on eastern Long Island (where it was still mostly potato fields) and playing a pickup game. Local kid named Carl from out there was up to bat, maybe a bit younger than my dad. Dad thinks he got him easy, throws him one pitch, it sails over his younger brother's head in center field. Next time up, Dad's mad and really puts the heat on it, kid hits it even further to dead center. This happens two more times, Dad trying hard each time, kid hitting it further each time. Dad says he knew then he was never gonna go very far with baseball.

Which was probably unfair, cause Carl's last name was Yastrzemski and he ended up being an 18 time All-Star for the Red Sox known universally as Yaz and was the AL MVP in 1967 with 44 HRs off major league pitchers.