Some of my fondest memories have problems.

I grew up in the western suburbs of Cleveland, Ohio, and so I grew up rooting for Cleveland sports teams. The Browns flirted with glory throughout the 1980s, the Cavaliers were strong enough to provide fodder for Michael Jordan’s legend-building, but more than anything, memories of my youth are attached to the Cleveland Indians.

The very first sporting events I attended were baseball games in Cleveland’s Municipal Stadium, a cavernous, crumbling Depression-era monument on the shore of Lake Erie. It was a dump, and I think I probably knew that on some level at the time, but it was also a marvel for a young child to behold — a place bigger than anywhere else I had ever seen, with birds flying in the rafters and creaky wooden seats you could bang to make even a crowd of 5,000 sound large. The baseball was garbage, but I certainly didn’t know that at the time. They were my hometown team.

In the ‘90s, right as I really came of age as a stats-obsessed tween sports fan, things took a sharp turn for the better. A new ballpark opened — a beautiful, modern edifice with all the bells and whistles and luxury boxes and none of the stink of failure. The team went from laughingstock to powerhouse almost overnight. A roster of crafty veterans and rising stars surged to 100 wins in a strike-shortened season in 1995. I still marvel at the collection of talent; three of the top 27 home run hitters in history batted 5-6-7 in the order that year. They brought the postseason to Cleveland for the first time in 41 years in a march full of dramatic moments but little suspense.

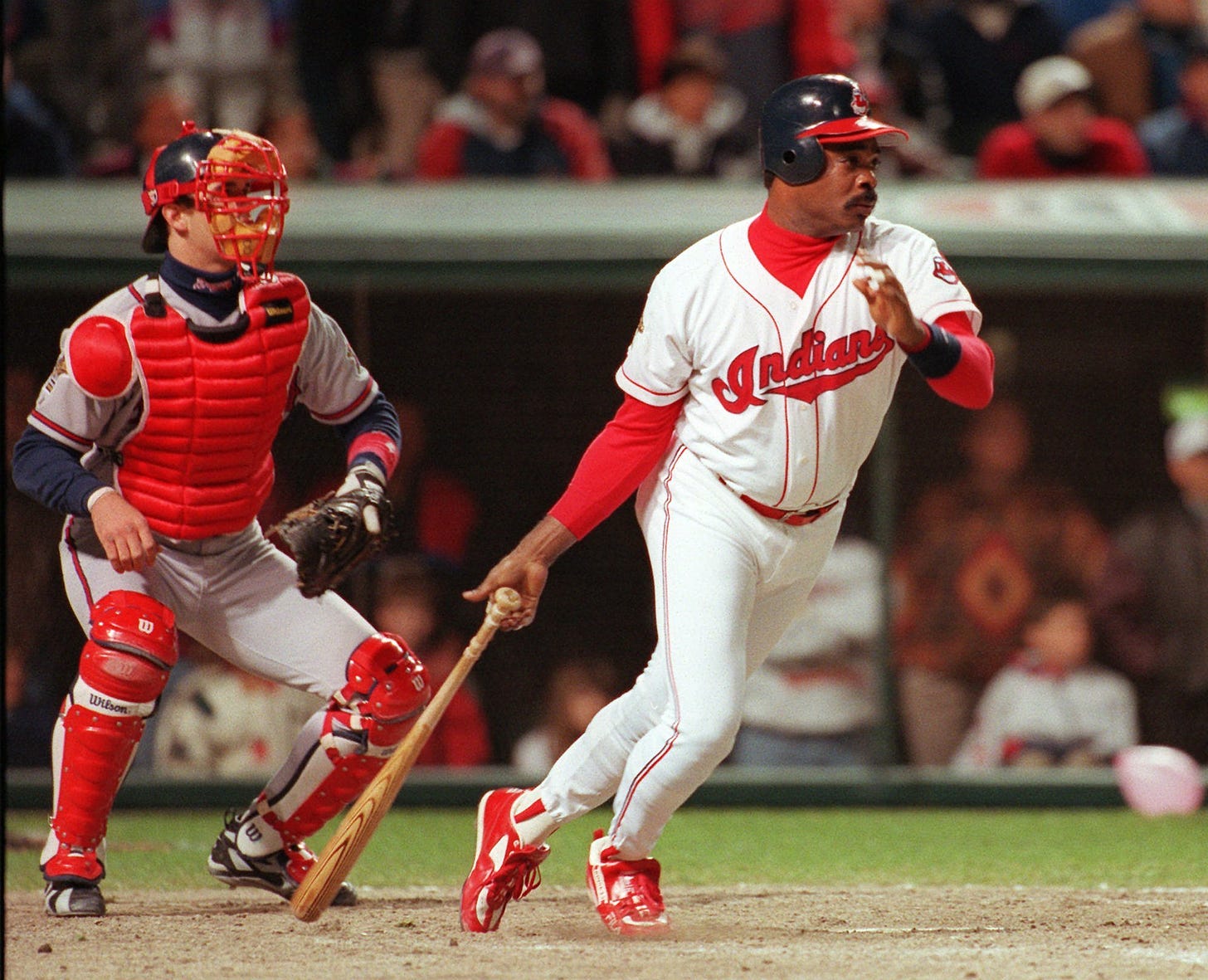

When they arrived in the World Series, through what seemed to 13-year-old me to be a miraculous turn of events, I got to go to the first home game. My father managed to snag three of the impossible-to-find tickets through his work, and in an act of generosity that still warms my heart 25 years later, he deferred so that my mother, older brother and I could attend. The energy around the stadium was like nothing I’d seen before and nothing I’ve seen since. It was unbelievable. The game was a tense, chilly, back-and-forth affair that went extra innings. When Eddie Murray lined a single up the middle in the bottom of the 11th, scoring pinch-runner Alvaro Espinoza and delivering the Indians’ first World Series win since 1948, I think I was lifted off the ground by jostling, jumping, screaming bodies for a full minute. The Indians went on to lose the series, but it was easily one of the greatest days of my life.

A memory like that is strong enough to endure change.

You can make whatever excuses you want for the team’s name, but in the end they’re just excuses. Some fans claim — almost certainly apocryphally — that the Indians were named to honor Louis Sockalexis, a player of Native American heritage who played three seasons for the city’s National League predecessor, the Cleveland Spiders, at the end of the 19th century. In reality, the team was likely named “Indians” because people weren’t terribly creative in naming sports teams 100 years ago. The choices usually boiled down to cat, dog, or stereotype of a systematically-persecuted people.

There are lots of things that used to be considered okay by a majority of people that aren’t now. Times change, slower than they should, and little amends are made for the misdeeds of the past. The least — and truly, I mean the absolute least — we can do is try to improve the things that require almost nothing of us than to admit an error. Changing the name of a sports team that borrowed an identity with no intent to honor it doesn’t return stolen land or undo any of the violence of the past. It doesn’t correct a historical wrong, but it goes the tiniest bit of the way toward at least admitting the wrong. Toward admitting the humanity of the people whose identity has been treated like a costume or a joke for longer than any of us have been alive.

I have a deep well of fond memories tied to this team, memories from which that imagery is inextricable, memories where the inexcusable cartoon of Chief Wahoo — a symbol the team officially distanced itself from several years ago, fortunately — is emblazoned on the caps and sleeves of my childhood heroes. I know that there are hundreds of thousands of other people for whom the same is true; people for whom this baseball team represents summer afternoons at the stadium with a parent or in front of a radio with a grandparent. People for whom the team represents a beloved friend or relative who died without ever seeing them win that World Series. Those memories will not go away if tomorrow or next week or next year the team that runs out on the field is the Spiders or Guardians or Rapids or Forest Cities.

I want to pass on my love of a baseball team to my children in the same way that my parents did to me. This team represents my hometown, a place I still consider an important part of my identity even though I haven’t lived there in over 20 years. I would prefer to pass on that love without perpetuating a slur, without continuing the most frivolous and easily-corrected part of a centuries-long series of historical wrongs. If changing the name allows one other fan to feel included, to feel that the team welcomes them as something other than a joke, then it’s worth it.

Doing so will not erase those afternoons with Mom or Dad or Grandpa. It will not undo the joy that loving a team has given you. The memories will survive.

Two years from now, I want to sit at a ballgame on a sunny post-pandemic summer afternoon in Cleveland, showing my children the ballpark where I had one of the greatest nights of my young life. I’ll point out the ‘party platforms’ that stand where they took out upper-deck seats and explain that I once lined up at Stop & Shop’s Ticketmaster kiosk in December hoping for a slim chance at buying those nosebleeds, in a baseball-obsessed moment when the whole next season would sell out before Christmas. I’ll show them the statue of slugger Jim Thome, whose bat-pointed-at-the-pitcher stance I still emulate when playing backyard wiffle ball. I’ll point out the spot where Rajai Davis’s home run landed, and how I jumped up and down while screaming silently at home because my three-week-old daughter was asleep in my arms.

If they ask why there are some people rooting for our team while wearing a different jersey with a different name, I can explain: that’s how it was done before, but now we’re doing things a little bit better. It was the least we could do. Yes, I agree Spiders is much cooler, and those people should get the cool new jerseys like we did.

It’ll be a new memory, and I look forward to making it.

— Scott Hines (@actioncookbook)

Cookbook can write. That language on what we do and don't do when we change a name was perfect.

Agree with everything except the last bit- Spiders sucks, and that memory should be let far in the past