It was a slow news weekend in America, and so I think today is a great time to talk about our summer reading lists.

Right?

Right. Let’s go with that.

Glad we agree.

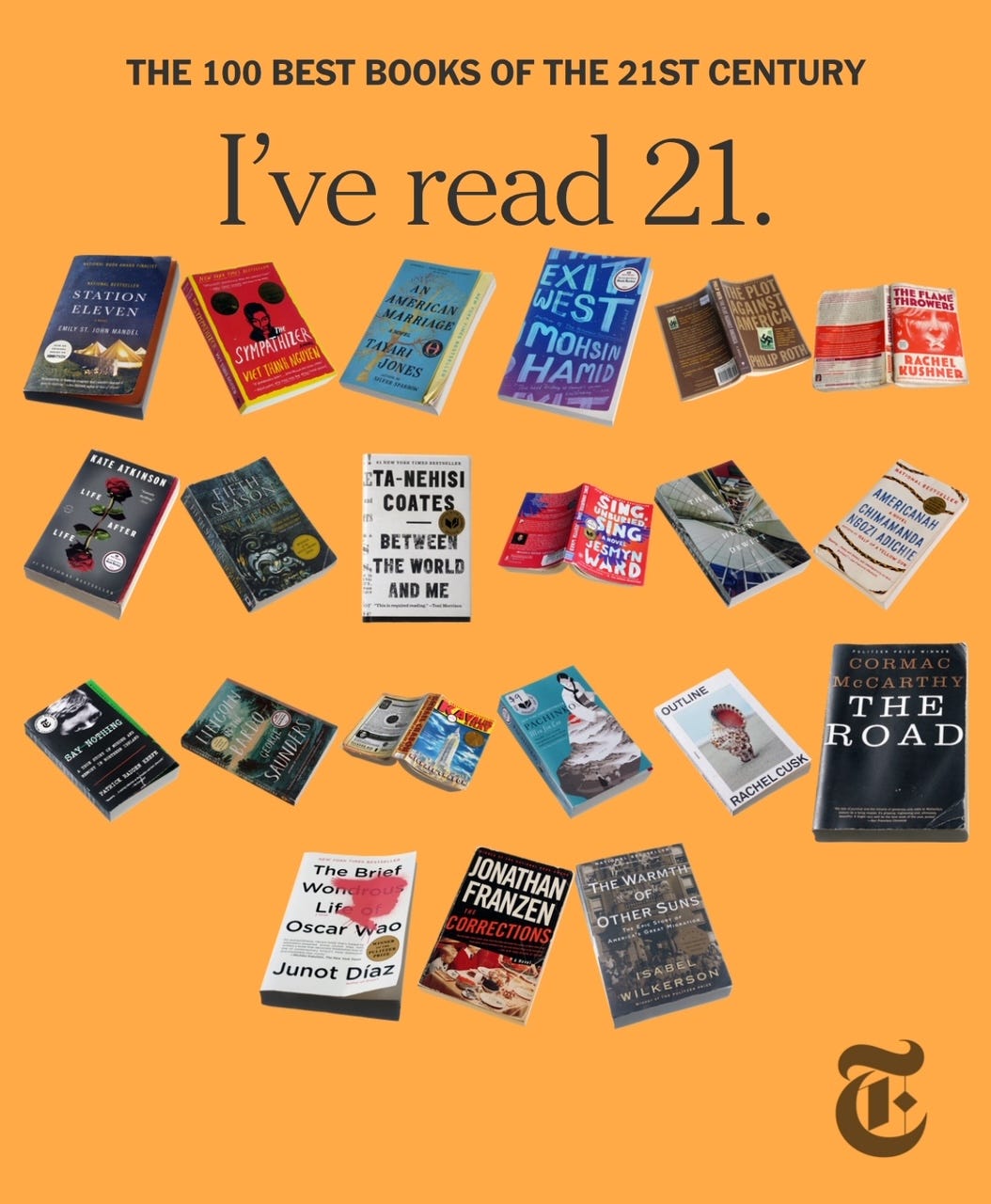

Last week, the New York Times—a crossword-puzzle-and-word-game-company that dabbles in news coverage, to varied results—rolled out their list of the “100 Best Books of the 21st Century”.

Obviously, that superlative is a bit premature, given that we’re slightly less than a quarter of the way through the 21st century. I mean, a “best college football teams of the 20th Century” list published in 1924 would’ve included Yale and Pitt.

The state of the media industry being what it is, though, there’s no sense sitting on your drafts.

Now, I’m not a literary critic by any stretch of the imagination, but I’d read 21 of the books on the Times’ list, and based on that decent sample size, I can’t take much fault with it. The books on the list that I have read range from pretty-good-if-not-great to genuinely-spectacular, and they’re fairly representative of what I’d expect a large outlet like the Times to produce.

(I like to talk more about things that I like than things that I don’t, so I will not dwell on the books that I think were over-ranked here.)

Book recommendations have long been a feature of The Action Cookbook Newsletter; I include one in (nearly) every Friday newsletter, and I’ve been doing so for more than five years now. That’s several hundred ACBN Book Club recs, all of which you can browse at my Bookshop affiliate page.

(I get a small commission if you buy from that link, but it’s more just a handy way for me to keep the recommendations organized.)

Today, I want to talk about a few great books that weren’t on the Gray Lady’s list.

Are they Great Books? [shrug] I dunno.

They’re pretty great in my book, and that’s all that I really care about.

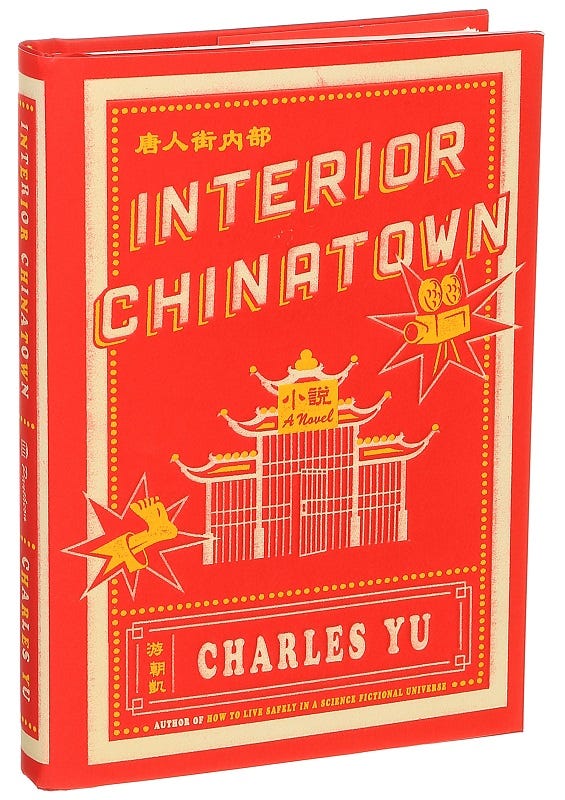

Interior Chinatown by Charles Yu

Interior Chinatown is a remarkable book, one that discards a straightforward novel structure and instead weaves between second-person narrative and screenplay, both centered around protagonist Willis Wu, a so-called “Generic Asian Man” who dreams of ascending the ladder to “Kung Fu Guy”.

Ever since you were a boy, you’ve dreamt of being Kung Fu Guy.

You are not Kung Fu Guy.

You are currently Background Oriental Male, but you’ve been practicing.

Maybe tomorrow will be the day.

It’s a stunning, brisk story, both sorrowful and sharply hilarious, that plays deftly with a host of themes from the marginalization, assimilation, and internalized racism facing Asian-Americans, the pain of aging and the terrifying joy of parenthood, and the lifelong struggle of immigrant families striving for success in a society that views race primarily as a binary that does not include them.

The best thing I can say about this book, and there are many good things I can say about it, is that every ten pages or so I had to set it down for a few minutes to digest a line so perfect it knocked the wind out of me. It’s short—266 pages that read much faster because of its format—but expertly, meticulously crafted, and not a word is wasted.

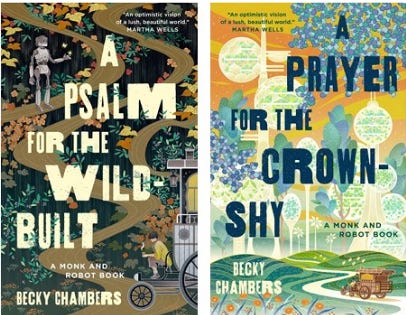

A Psalm for the Wild-Built / A Prayer for the Crown-Shy by Becky Chambers

Technically this is two books, but I’m counting them as one, since they’re about the legnth of a typical novel put together. This pairing—the Monk & Robot duology—is unlike pretty much anything else that I’ve ever read.

The story takes place in Panga, a society where robots once served the needs of humanity much as they do for us now. Several hundred years ago, though, the robots gained sentience and laid down their tools. A departure was negotiated, and one day, the robots walked en masse into the woods, and have not been seen by humans for centuries. One day, Sibling Dex, a solitary monk who travels the roads of Panga serving tea and comfort to the humans of Panga, unexpectedly encounters a robot who has returned in search of the answer to a difficult question: what do humans need?

It’s a richly-imagined and beautifully-conjured sci-fi/fantasy world that’s mercifully low-stress while not being the least bit flimsy. They’re very nice books.

An Immense World by Ed Yong

It’s rare that a non-fiction book can cause me to see the world around me in a completely new light, but this delightful book did exactly that. Yong explores the complex sensory worlds that different animals inhabit—worlds that exist in the same space as our own, but with perceptions so vastly different from our own that they might as well be parallel universes right under our own (inferior) noses.

He explains the semiotic concept of umwelt, or the “self-centered world”—that is, the world that an organism inhabits as shaped by its own ability to perceive. A dog or elephant or mouse or rattlesnake’s view of the world is shaped by senses that often differ greatly from our own; what appears to be a featureless expanse of open ocean to us might be a rich and varied landscape of smells to a tube-nosed sea bird.

Many of the things we might consider ‘extra-sensory’—for instance, animals’ ability to sense oncoming storms before humans—are actually purely sensory, Yong argues, products of one or more of the five classical senses performed at a far higher level than our own.

It’s a genuinely fun read, and one that can spark fresh wonder in a jaded mind.

There’s Always This Year by Hanif Abdurraqib

There are certain writers who I will trust to read on absolutely anything they choose to write about, and one of those writers is Hanif Abdurraqib.

I first got turned onto his writing with the 2017 essay collection They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us, and have since read his masterful A Little Devil In America: Notes in Praise of Black Performance and Go Ahead in the Rain: Notes to A Tribe Called Quest.

Abdurraqib crafts masterful poetic yarns, and I don’t always know where he’s going halfway through an essay but the destination always makes sense when we get there and the journey itself is always a thrill. I strongly debated which of his books I wanted to include here, but his latest might just be my favorite of the lot, a beautifully-meandering meditation on life centered on basketball in and around Abdurraqib’s Ohio home, from Columbus high school greats to the career of LeBron James.

I am comfortable in saying that I’m not a good enough writer to describe this book in a way that would do it justice; it had me riveted throughout.

Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi

Here’s a book I genuinely wouldn’t have been surprised to see on the Times’ list, and frankly I’m a little disappointed didn’t make it. It’s an epic family story, one that follows the descendants of two sisters from present-day Ghana separated by the Atlantic slave trade, jumping forward a generation with each chapter.

It’s a big, ambitious story, at turns heartbreaking and uplifting, and Gyasi pulls it off without it feeling like a literary contrivance.

Hell Is a World Without You by Jason Kirk

If you’re reading this newsletter, there’s a good chance that you’re already familiar with Jason Kirk, and with the novel he put out last year. Jason and I both made our internet names at SBNation (though we never worked directly together), and we share partially-overlapping audiences for our work.

Still, this book more than merits inclusion here, and I’m doing so for those of you who may not already know about it (or who do, but haven’t read it yet).

Hell Is a World Without You is a millennial coming-of-age story set within the American evangelical church—a world of youth groups and thrice-weekly church services, accountability circles and constant fear of damnation. Kirk’s protagonist Isaac wrestles with the apparent suicide of his father, a man church elders tell him is now burning in hell forever, and the sense that he’ll be consigned to the same fate if he’s not perfect in ways that don’t feel perfect to him.

I was not raised evangelical; I have seen many people who were exclaim that this book perfectly captured their adolesence in a way they did not think possible. As an outsider to this world, I was no less stunned—it gave me startling insight into the lives of my evangelical classmates, many of whom I saw clearly in his characters.

Earlier this year, I conducted an interview with Jason, and you can read that here:

Why Fish Don’t Exist by Lulu Miller

How do you have hope in a world of no promises?

That’s a central question in this fascinating and unusual book from Peabody Award-winning NPR science reporter Lulu Miller. Not quite a biography and not quite a memoir, the book explores the compulsion to “make order in a world ruled by chaos”. Miller sees a kindred spirit in the 19th-century academic David Starr Jordan, the founding president of Stanford University and one of the foremost taxonomists of his time.

Jordan was prolific in his study of nature, identifying and classifying numerous creatures in a decades-long career, many of them fish. He persevered despite multiple personal tragedies; a lightning strike-ignited fire that destroyed one of his early labs, losing his first wife and favorite daughter to separate illnesses, and—perhaps most notably—the 1906 San Francisco earthquake destroying his carefully-curated collection of specimens gathered from all over the world.

As Miller describes it:

Imagine seeing 30 years of your life undone in one instant. Imagine whatever it is you do all day, whatever it is you care about, whatever you foolishly pick and prod at each day, hoping against all signs that suggest otherwise that it matters. Imagine finding all the progress you have made on that endeavor smashed and eviscerated at your feet… in that 47 seconds, Genesis had been reversed; his meticulously-named fish had become an amorphous unknown, again.

Miller interlaces this story with experiences from her own life—a broken relationship, a teenage suicide attempt, an emotionally detached father who taught her that the world was devoid of meaning. She finds solace in Jordan’s toil against chaos, but ultimately struggles with his desire to name and categorize everything, an impulse that shows its ugly side in his support of eugenics.

It’s a fascinating book that unfolds in wholly unexpected and beautiful ways, digging into some weighty philosophical territory without veering off its central story.

Across the River: Life, Death and Football in an American City by Kent Babb

Where Abdurraqib’s book above is a complex meditation on sports and life, this book is as straightforward as sportswriting can come—but it’s a terrific achievement in journalism, a cinematic epic of a story. The book follows the Cougars of Edna Karr, a magnet high school in east New Orleans, through their 2019 football season. Under the tutelage of a Karr alumni and offensive mastermind in head coach Brice Brown, the Cougars are pursuing their fourth straight state championship, but they face a myriad of struggles.

The players largely hail from Algiers, a violence-plagued neighborhood on the west bank of the Mississippi River. They face poverty, incarcerated or dead parents, and the constant threat of gun violence in one of America’s most trouble cities.

For Brown, this specter looms large; a beloved former quarterback for his Karr teams was gunned down in a murder that remains unsolved. A man with big dreams, Brown feels trapped between his own career ambitions and the feeling that he cannot leave his “Karr Men” behind.

This is an exceptional, exceptional piece of sportswriting and storytelling, one I would put on a par with other classics of the genre like H.G. Bissinger’s Friday Night Lights. It is broad, detailed, thoughtful, and genuinely cinematic; a scene late in the book recounting the end of a playoff game had my hands sweating as though I were there.

No One Is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood

This is an odd book, but I mean that in the best possible way.

It’s a lightly structured novel; the first half is largely dedicated to the unnamed protagonist’s experience with “the Portal”, a proxy for our own social media.

We’re given dryly-hilarious descriptions of her interactions within the portal—the nonsensical humor, actions and discourse it engenders—all things that will sound extremely familiar to anyone as online as me. It’s laugh-out-loud funny, a description I use sparingly and literally—I was genuinely laughing out loud at much of it—and it also kind of make me want to disconnect and go live in the woods.

When a tragedy touches her family, the narrator is jarred into thinking about things other than “can dogs be twins” and such social-media ephemera, and that’s where things shift: a book that starts out wildly silly becomes deeply moving.

Crying In H Mart by Michelle Zauner

I’ll wrap up my list at ten books—sorry, I’m not getting to 100 myself, at least not today—and end with this memoir from Michelle Zauner. Zauner—also known for her work as the lead singer and songwriter of indie band Japanese Breakfast—spins a lovely and heartbreaking story of love and loss.

The story centers primarily on Zauner’s complicated relationship with her mother, and her mother’s illness and death from cancer at the age of 56, but it fans out into a much larger examination of cultural identity, often channeled through food.

Zauner’s mother was Korean-born, her father American, and she often struggled to define herself fully in either world. In between stories of her mother’s strict expectations for her conflicting with her own artistic dreams, Zauner lyrically and vividly recalls meals her mother would prepare, and recounts her own attempts to recreate them after losing her.

As I noted in my original review of the book, I listened to the audiobook version which is narrated by Zauner herself. As an experienced stage performer reading her own words, it brings a new level to the work, and I really think it’s the best way to receive it.

This is hardly a comprehensive list, but I hope there’s something on here that you’ll pick up and enjoy yourself.

In the meantime, I love getting recommendations from readers—heck, some of the books on this list came directly from you all. Is there a book you’d like to trumpet? Something that should’ve made the Times’ list, or something you just can’t believe your pal Action Cookbook hasn’t read yet? Shout about it!

(Fine, this was all just a clever ruse to refill my own reading list.)

—Scott Hines (@actioncookbook)

/pounds table

MONK AND ROBOT. MONK AND ROBOT. I'm glad you love those books as much as I did.

Finally getting around to Station 11, and it's really good so far.

I just finished RF Kuang's Babel and loved it.

It balances being an unsubtle critique of colonialism with a love of languages, a great core group of characters, and some magic on the side.