Who lives in that building, anyway?

A story of famous architects, forgotten buildings, and the life in between.

Good morning! Welcome back to The Action Cookbook Newsletter. There’s something I’ve decided to try periodically around here, which is to write about architecture, as I’m an architect in my daily life. Last week, I wrote about Crosley Tower, the solid concrete tower that looms over the University of Cincinnati’s campus. Today, I’m talking about much smaller, older building.

You wouldn’t know it to look at the place.

On the far edge of Manhattan’s Upper West Side, there’s a boarded-up building. Blink and you’ll miss it — twenty-four feet wide, five stories tall, it’s wedged in between two massive, blocky co-op buildings much taller, wider and grander than it. It’s an afterthought, but it didn’t start out that way.

We have to go back more than a century to understand.

When Manhattan’s wealthiest residents were first striking north toward the island’s upper reaches in the late 19th century, this neighborhood wasn’t one of tall towers or bulky apartment blocks, but instead of stately townhouses meant to show off individuals’ success and taste. There could have been no grander gesture than to have a home built by the partnership of McKim, Mead and White, perhaps the pre-eminent architects of that era. Students of Paris’s neoclassical-influenced École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, they delivered grandeur to America’s growing cities with projects of a massive scale.

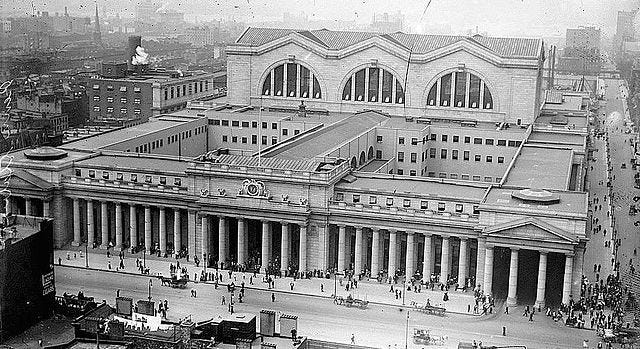

New York’s (original, above-ground) Pennsylvania Station, the Brooklyn Museum, the Washington Square Park arch, the Boston Public Library, the Rhode Island State House, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History and many more buildings bore their mark. One of the partners, Stanford White, would gain a special place of prominence in the American memory in 1906, when the enraged husband of his teenage lover Evelyn Nesbit shot and killed him at a party on the roof of (then) Madison Square Garden, launching the first of the 20th century’s many “Trial(s) of the Century”.

The point is: they were a big deal.

In one their much lesser-known commissions, they designed a row of six townhouses on the corner of West 83rd Street and West End Avenue. As the neighborhood outgrew its single-family footprints, the five houses facing 83rd Street would eventually be demolished to make way for one of those big apartment blocks. The little house on West End Avenue remained. A New York Times article from 2003 documented some of the history: the building passed through a few hands, wealthy and prominent people, before being subdivided into apartments in the 1930s. The elaborate brickwork would crumble and be plastered over, the entrance and windows altered. There would be little left to suggest that the building came from the most famous drafting tables of its time.

There’s a plan to bring it back now, though. Some of New York’s top real estate brokers have engaged a prominent architect of their own in the hopes of selling a vision of what the building could be. Full plans are online, showing how you — yes, you — could have “multiple bedrooms with ensuite baths + powder rooms, an endless swimming pool, theatre, library, stone fireplaces, game room, roof deck, and garden,” all for the completely affordable price of $7.5M.

This is, of course, entirely normal for New York City real estate in the 21st century: grandiose plans in search of a buyer, someone who can invest millions into an address, never live there, and likely profit handsomely off its sale in the future. A townhouse built on spec by the preferred architects of two lifetimes ago, forgotten and neglected, ravaged by time and fate, soon to be restored to its purportedly-rightful stature by an architect of present-day prominence. The cosmic ballet goes on.

That’s not the whole story. The only buildings in Manhattan with no story to tell are the new ones, the vacant glass spires punching up through the skyline to serve as little more than offshore accounts for the world elite. The lesser buildings, the forgotten buildings, the just plain crappy ones like the house on West End Avenue — they have stories of their own.

I know this because I lived in it.

We’d moved to that building after being priced out of a Brooklyn apartment. Within mere minutes of seeing the tiny little second-floor patio attached to the 400-square-foot box of an apartment, we signed a lease. It was a squeeze to fit two people and a dog in, but we adored it. Sunlight. Location. The chance to grill out in Manhattan. We made it work. We once had forty people in it for a party. (We used to throw good parties. Time comes for people as much as for buildings). Of course, we were hardly the interesting ones in the building.

A man on the first floor, who we’d first come to know for his fastidiousness in sorting recycling (and expectation of the same from others), we’d later find out was the last non-military American to leave Vietnam after the war, having founded a rescue mission that housed and protected hundreds of orphaned street children.

The woman we shared a hallway — and an impossibly-thin, not-at-all soundproof bathroom wall with — who would serve as a sobering lesson in what it would be like to deal with Phoebe from Friends if she were an actual person. We became embroiled in a long-running, multi-party fiasco over loudly-humming refrigerators that I’m still far too annoyed about to describe in full.

An artist and a historian. A charming college kid we’d later find out to be the son of a famous actress. Two apartments on the uppermost floors were rent-controlled, inhabited for decades by now-elderly men living on their own. One day, one of these men told us his story. A young teenager from Hungary, a Jewish boy who survived when his older brother was killed. A survivor of the concentration camps. He told us the story of how his grasp of languages saved him one day, and got a Russian soldier (a fellow captive, but of a higher caste) beaten by their German captors in his stead. He told it with a well-earned laugh. He’d gotten out, made it in America.

He’d lived in the building for over forty years.

In December 2013, the building was ravaged by a massive fire. It started in one of the older men’s apartments, and swept through the two upper floors. The front of the building was flooded by the hours-long firefight. As windows shattered and rained down on our patio, I waited in our miraculously-mostly-unaffected apartment with our dog, ordered to shelter in place by firefighters until they were ready for me. Thankfully, no one was killed, but the building was rendered uninhabitable. No one’s lived in it since.

The story the brokers will tell their hypothetical buyers is one of restoration. This place was once great, and with you it can be great again. Money always tells the story it wants, and it leaves out a lot of details. A building is defined by a narrow set of factors: who designed it, who restored it. There’s the desire to describe every building — and the city at large — as the work of individual artists shaping a static, vision of the built environment, untainted by human life. As an architect, I’ve been guilty of it, too. I was delighted when I found out about the McKim, Mead and White connection to my little apartment. Think what this place must’ve looked like.

What’s absent from this thinking is a understanding of the true life of a building.

Would the restoration of this building be complete when the brickwork is re-pointed, the windows replaced, and a new entrance installed? When there’s a theater in the basement and Apartment 2R becomes a “piano gallery”, when an entire floor is turned over to a private swimming pool, will the 19th-century vision of luxury be redeemed?

Perhaps instead we should consider the true restoration of a building to be when the architect’s vision is taken away from them, claimed by the organic life of a city, tarnished and tainted by the lives lived inside and around it.

Maybe the building was never forgotten. Maybe we were just asking the wrong people.

-- Scott Hines (@actioncookbook)